Mercurial Lamb: A Narrative of Collaborative Mutation

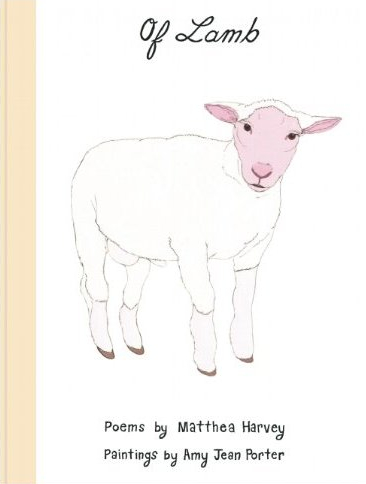

Eric Kim reviews Matthea Harvey's "adult-children's book" Of Lamb, a new erasure put out by McSweeney's.In their new release, Of Lamb (McSweeney’s, 2011), poet Matthea Harvey and painter Amy Jean Porter collaborate on a story that haunts, delights and surprises all at the same time. Through vibrant paintings that complement a dark, tilted narrative, Harvey and Porter have concocted, as Rae Armantrout calls it, an “adult-children’s book [...] each page like a Valentine’s Day chocolate with one drop of arsenic.”Inspired by Jen Bervin’s Nets and Tom Phillips’s A Humument, Harvey’s erasure of David Cecil’s A Portrait of Charles Lamb is eerie yet coherent, foreign yet familiar—in her own words, “an irreverent and warped retelling of the nursery rhyme.” Mary, essentially, had a little lamb, but they did more than just go to school together: “They pin’d and hungr’d after bodily joy/ Lamb and Mary met in whatever room happened to be closest/ Who would not be curious to see the pictures?” Carefully balancing abstract nuances undoubtedly facilitated by the erasure process (“Vacillating Lamb owed everything, owed nothing to love”) with concrete plot points that tie the whole thing together into a narrative (“Lamb found Mary crying in the hedge”), Harvey showcases through Of Lamb the innovative, subtle capabilities of erasure poetry to mutate the original for the better.The point here is mutation: it is not the mere recreation of the nursery rhyme that spellbinds readers; it is those remnants of the familiar story that have been warped in the most disturbing sense, from children’s song to bestial tragedy, from linear narrative to disjointed, kaleidoscopic experience—those moments are what make Harvey’s erasure a complete success, a modern chronicle of change through the seasons to an eventual coda: “He could not stop the clouds or the sun/ Lamb thought conclusions were all alike.” The process of whiting out, of erasing significant portions of the original text in order to understand a different kind of narrative, simulates not only Lamb’s snowballing physical and mental disintegration by the end (“Lamb’s mind struggling, forgetting [...] His figure had grown dim”), but also Mary and Lamb’s mercurial relationship, the fragmental shift from love to loss.Porter’s paintings often highlight this mercuriality: Lamb is a different color in each drawing. His fleece is not “white as snow,” but shades of burgundy, indigo and emerald, each reflexive of the mood of that specific page. But the most curious moments in the book are when Porter’s paintings instead complicate Harvey’s text. For example, to “Mary shut his eyes to the future and ardently turned to animal satisfactions,” Porter paints Mary devouring a piece of flesh behind Lamb’s back. Meat eating, a strident motif in the book, is at first Porter’s interpretation of Harvey’s text: “animal satisfactions” does not seem to point to meat eating so readily. But later, Lamb in fact reveals, “Should I tell you I watched her eating a bit of cold mutton in our kitchen?” Porter’s accompanying painting illustrates Mary licking a pink lamb popsicle, then three pages later, lamb licking from the ground that very popsicle melted. Harvey’s coupled text at this point is less obvious: “Year by year he appeared fatter, but Lamb was not full of fun.” Such an impact of Porter’s paintings on Harvey’s seemingly abstract words, and vice versa, suggests the need to read Of Lamb not as a mere poem with accompanying illustrations, but as a collaboration of the two mediums, each as much a part of the narrative as the other.This duality makes it difficult to define what Of Lamb is about—because semantically the words say one thing while the paintings say another. But they certainly work together, as Harvey puts it, “like a game of telephone, or an archeological site, each layer taking something from the layer before and transforming it.” Harvey’s textual mutation interacts with Porter’s illustrations in a way that resists meaning-making and facilitates encountering, unexpectedly experiencing Mary and Lamb page by page. Perhaps the point here, then, is not to inject meaning into Harvey and Porter’s chocolate, but rather to taste the injected arsenic, to enjoy the mutation as the drug it is.Eric Kim, Poetry Editor

Eric Kim reviews Matthea Harvey's "adult-children's book" Of Lamb, a new erasure put out by McSweeney's.In their new release, Of Lamb (McSweeney’s, 2011), poet Matthea Harvey and painter Amy Jean Porter collaborate on a story that haunts, delights and surprises all at the same time. Through vibrant paintings that complement a dark, tilted narrative, Harvey and Porter have concocted, as Rae Armantrout calls it, an “adult-children’s book [...] each page like a Valentine’s Day chocolate with one drop of arsenic.”Inspired by Jen Bervin’s Nets and Tom Phillips’s A Humument, Harvey’s erasure of David Cecil’s A Portrait of Charles Lamb is eerie yet coherent, foreign yet familiar—in her own words, “an irreverent and warped retelling of the nursery rhyme.” Mary, essentially, had a little lamb, but they did more than just go to school together: “They pin’d and hungr’d after bodily joy/ Lamb and Mary met in whatever room happened to be closest/ Who would not be curious to see the pictures?” Carefully balancing abstract nuances undoubtedly facilitated by the erasure process (“Vacillating Lamb owed everything, owed nothing to love”) with concrete plot points that tie the whole thing together into a narrative (“Lamb found Mary crying in the hedge”), Harvey showcases through Of Lamb the innovative, subtle capabilities of erasure poetry to mutate the original for the better.The point here is mutation: it is not the mere recreation of the nursery rhyme that spellbinds readers; it is those remnants of the familiar story that have been warped in the most disturbing sense, from children’s song to bestial tragedy, from linear narrative to disjointed, kaleidoscopic experience—those moments are what make Harvey’s erasure a complete success, a modern chronicle of change through the seasons to an eventual coda: “He could not stop the clouds or the sun/ Lamb thought conclusions were all alike.” The process of whiting out, of erasing significant portions of the original text in order to understand a different kind of narrative, simulates not only Lamb’s snowballing physical and mental disintegration by the end (“Lamb’s mind struggling, forgetting [...] His figure had grown dim”), but also Mary and Lamb’s mercurial relationship, the fragmental shift from love to loss.Porter’s paintings often highlight this mercuriality: Lamb is a different color in each drawing. His fleece is not “white as snow,” but shades of burgundy, indigo and emerald, each reflexive of the mood of that specific page. But the most curious moments in the book are when Porter’s paintings instead complicate Harvey’s text. For example, to “Mary shut his eyes to the future and ardently turned to animal satisfactions,” Porter paints Mary devouring a piece of flesh behind Lamb’s back. Meat eating, a strident motif in the book, is at first Porter’s interpretation of Harvey’s text: “animal satisfactions” does not seem to point to meat eating so readily. But later, Lamb in fact reveals, “Should I tell you I watched her eating a bit of cold mutton in our kitchen?” Porter’s accompanying painting illustrates Mary licking a pink lamb popsicle, then three pages later, lamb licking from the ground that very popsicle melted. Harvey’s coupled text at this point is less obvious: “Year by year he appeared fatter, but Lamb was not full of fun.” Such an impact of Porter’s paintings on Harvey’s seemingly abstract words, and vice versa, suggests the need to read Of Lamb not as a mere poem with accompanying illustrations, but as a collaboration of the two mediums, each as much a part of the narrative as the other.This duality makes it difficult to define what Of Lamb is about—because semantically the words say one thing while the paintings say another. But they certainly work together, as Harvey puts it, “like a game of telephone, or an archeological site, each layer taking something from the layer before and transforming it.” Harvey’s textual mutation interacts with Porter’s illustrations in a way that resists meaning-making and facilitates encountering, unexpectedly experiencing Mary and Lamb page by page. Perhaps the point here, then, is not to inject meaning into Harvey and Porter’s chocolate, but rather to taste the injected arsenic, to enjoy the mutation as the drug it is.Eric Kim, Poetry Editor