Hello friend. How are you? It’s been a long time. It’s been over a year since I last assigned you a book to read. Did you manage to power through that 192-page book in the 388 days it has been since I last spoke to you? I hope so. I didn’t want come back too soon and spook you off. I just want you to be comfortable.For those of you who were able to finish Civilwarland in Bad Decline, I have another recommendation. For the rest of you who need another 388 days, take your time. I’ll check back with you on December 2, 2013.Swimming to Cambodia is a book by a fella named Spalding Gray. He was asked to play a role in the The Killing Fields, a film about the Cambodian Civil War. Swimming to Cambodia juxtaposes his adventures and shenanigans while filming a Hollywood movie against the real story and history of the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia, and the result is simultaneously gut busting and gut wrenching.I bet you’re asking yourself “Hey Conor, I get why you’d recommend this to a smarty-pants who likes books, but why would you recommend it to somebody who doesn’t like to read?” I’ve got three major selling points for you my friend.It’s funny. Spalding Gray has a mastered a sort of dirty neuroticism that reminds me of the hypothetical baby-fusion of Woody Allen, Harmony Korine, and Hunter Thompson. A decent-sized portion of this book deals with Gray, a neurotic and gawky man in his 40’s, trying to conquer his fear of the ocean while high on opiates. It is exactly as good as it sounds.It’s short. The edition I’m holding in my hand is a scant 133 pages, and when you take into account how large the type and how small the pages are, the final page count becomes even less intimidating. I managed to plow through this in two hours while waiting for a train home before Hurricane Sandy.It’s smart. The parts of Swimming to Cambodia that aren’t dealing with a man stoned out of his gourd coping with his hydrophobia are extraordinarily insightful and powerful. If you were to ask me before this book what the Khmer Rouge was, I probably would’ve responded “A video game character.” Though the subject matter is often lighthearted, Gray is capable of switching gears instantaneously. The story takes wild nosedives that leave you at the precipice of despair, before Gray finally pulls up on the controls and resumes talking about wanting to marry a hooker.Look. I’m not a dummy. I know how these things work. I assign this book to you, and you just sit around on reddit procrastinating until 2 AM, when you panic, realize you won’t be able to read the book, and desperately scramble to look for a movie version. Then you leaf through Google and Sparknotes, hoping to find somebody who has made a list of the differences between the film and the book, so that you can come back to me appearing as prepared as possible.Rest easy my friend: I’ve got you covered. Swimming to Cambodia was originally written as a monologue. It was designed from the get-go to be watched.

"He broke it all down to a table, a glass of water, a spiral notebook and a mic. Poor theatre—a man and an audience and a story. Spalding sitting at that table, speaking into the mic, calling forth the script of his life from his memory and those notebooks. A simple ritual: part news report, part confessional, part American raconteur. One man piecing his life back together, one memory, one true thing at a time. Like all genius things, it was a simple idea turned on its axis to become absolutely fresh and radical."

-Theatre Director Mark Russell on Spalding Gray

Jonathan Demme, the man who directed Silence of the Lambs and Philadelphia adapted Swimming to Cambodia for the screen. However, this is not a scenario in which you’d have to scramble around the Internet trying to find out any differences between the book and the film. I’ll make this easy for you: there are none. The exact same thing you see on screen is right there in your book.Now, don’t get me wrong: I’m not necessarily suggesting that you only go and watch the film. There are a few things that might go over your head if you’re not paying full attention, and it definitely helps to be able to flip back. By no means am I saying that this book will make you feel dumb, but as it deals with Cambodia, a place I’m assuming you’re not familiar with, sometimes the names and other proper nouns can get confusing. It’s not a particularly difficult book, but it will definitely keep you on your toes.I’ve saved my trump card for last. If I haven’t won you over yet, listen up. There’s a story in the book about John Malkovich telling a dirty joke. So, get on that man.-Conor Burnett, Prose Editor

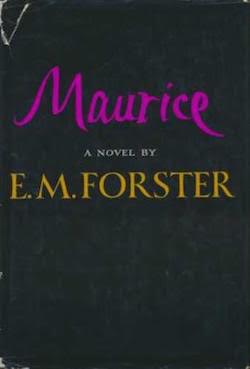

Written in 1913 but only published posthumously in 1971, Maurice was well ahead of its time in its nuanced depiction of a young man discovering and coming to terms with his sexuality. While Forster carefully examines the difficulties of identity and love, Maurice is ultimately founded on the belief that same-sex relationships have the capacity to be profound, beautiful and happy—a radical thesis for a novel written when men were still routinely arrested and imprisoned for having sex with other men.

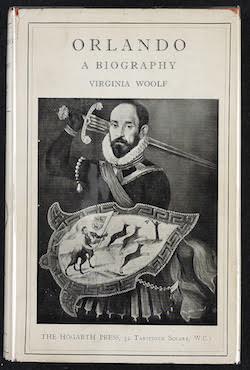

Written in 1913 but only published posthumously in 1971, Maurice was well ahead of its time in its nuanced depiction of a young man discovering and coming to terms with his sexuality. While Forster carefully examines the difficulties of identity and love, Maurice is ultimately founded on the belief that same-sex relationships have the capacity to be profound, beautiful and happy—a radical thesis for a novel written when men were still routinely arrested and imprisoned for having sex with other men.  Subtitled “A Biography,” Orlando was written as a paean to Woolf’s friend and erstwhile lover, the aristocratic Vita Sackville-West. With typical élan, Woolf transforms Sackville-West into the novel’s eponymous protagonist, a sex-changing immortal who begins as an Elizabethan nobleman and ends as a successful female author in ‘the present day’ (that is to say, 1928). Traversing three hundred years of Orlando’s life, Woolf relentlessly questions conventional notions of history, authorship, gender and sexuality. Nightwood - Djuna Barnes (1936)

Subtitled “A Biography,” Orlando was written as a paean to Woolf’s friend and erstwhile lover, the aristocratic Vita Sackville-West. With typical élan, Woolf transforms Sackville-West into the novel’s eponymous protagonist, a sex-changing immortal who begins as an Elizabethan nobleman and ends as a successful female author in ‘the present day’ (that is to say, 1928). Traversing three hundred years of Orlando’s life, Woolf relentlessly questions conventional notions of history, authorship, gender and sexuality. Nightwood - Djuna Barnes (1936) Contained in a deceptively slim volume, Nightwood is a superbly stylized portrait of a doomed lesbian relationship in the bohemian Paris of the interwar years, explicated through the head-spinning speeches of Dr. Matthew-Mighty-grain-of-salt-Dante-O'Conner (who is just as campy as his name suggests). This modernist masterpiece was lauded by T.S. Eliot as “so good a novel that only sensibilities trained on poetry can wholly appreciate it.” Notre Dame des Fleurs/Our Lady of the Flowers - Jean Genet (1943)

Contained in a deceptively slim volume, Nightwood is a superbly stylized portrait of a doomed lesbian relationship in the bohemian Paris of the interwar years, explicated through the head-spinning speeches of Dr. Matthew-Mighty-grain-of-salt-Dante-O'Conner (who is just as campy as his name suggests). This modernist masterpiece was lauded by T.S. Eliot as “so good a novel that only sensibilities trained on poetry can wholly appreciate it.” Notre Dame des Fleurs/Our Lady of the Flowers - Jean Genet (1943) Similarly to Nightwood, this novel renders the Parisian underworld in prose so rich and revelatory it practically creates a new class of literature. The lives and loves of its central characters—sex workers, trans women, and teenage murderers, all bearing charming monikers like Divine and Darling Daintyfoot—are unspooled by a capricious narrator who creates the world of the novel while masturbating in his prison cell (!!!). The Charioteer - Mary Renault (1953)Renault, having worked as nurse at a British military hospital during the Second World

Similarly to Nightwood, this novel renders the Parisian underworld in prose so rich and revelatory it practically creates a new class of literature. The lives and loves of its central characters—sex workers, trans women, and teenage murderers, all bearing charming monikers like Divine and Darling Daintyfoot—are unspooled by a capricious narrator who creates the world of the novel while masturbating in his prison cell (!!!). The Charioteer - Mary Renault (1953)Renault, having worked as nurse at a British military hospital during the Second World  War and later emigrated to South Africa to live with her female partner, was uniquely equipped to write this novel, which follows a British soldier who falls in love twice over as he recovers from a combat wound. With equal measures of heartfelt psychological insight and cutting social observation, The Charioteer struggles with the tensions between idealism and reality, individualism and community, and innocence and experience. Another Country - James Baldwin (1962)An earlier novel of Baldwin’s, Giovanni’s Room, is often hailed as a masterpiece of gay literature, but while Giovanni’s Room is a claustrophobic investigation of one man’s psychology, Another Country seems to encompass an era.

War and later emigrated to South Africa to live with her female partner, was uniquely equipped to write this novel, which follows a British soldier who falls in love twice over as he recovers from a combat wound. With equal measures of heartfelt psychological insight and cutting social observation, The Charioteer struggles with the tensions between idealism and reality, individualism and community, and innocence and experience. Another Country - James Baldwin (1962)An earlier novel of Baldwin’s, Giovanni’s Room, is often hailed as a masterpiece of gay literature, but while Giovanni’s Room is a claustrophobic investigation of one man’s psychology, Another Country seems to encompass an era.  The characters are gay, straight, bisexual, questioning and in denial; white and black; working-class and middle-class and destitute and wildly successful. In a rhythm reminiscent of jazz, the novel traces the cast as they move in and out of each other’s lives, coupling and splitting up and getting back together, rising and falling in fortune—but always circling around the specter of a character who commits suicide at the end of the novel’s first act.

The characters are gay, straight, bisexual, questioning and in denial; white and black; working-class and middle-class and destitute and wildly successful. In a rhythm reminiscent of jazz, the novel traces the cast as they move in and out of each other’s lives, coupling and splitting up and getting back together, rising and falling in fortune—but always circling around the specter of a character who commits suicide at the end of the novel’s first act.