A Snowed-In Review of "A Little White Shadow" by Mary Ruefle

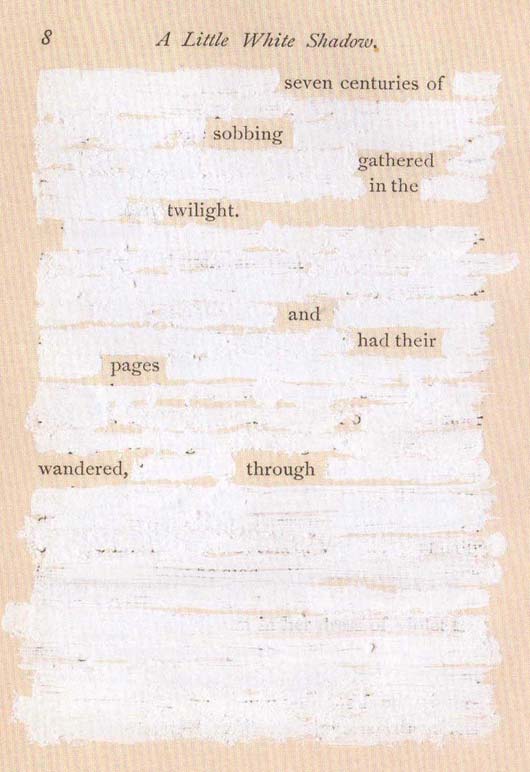

By Amanda Montell Mary Ruefle's "A Little White Shadow" may not be breaking news amongst poetry readers; but, when the weather outside is frightful and you're in the mood to stay cozily inside, rediscovering your own bookshelf can be just as exciting as diving into a stack of new-releases. Ruefle's 5-by-4-inch book of erasures, so small and sweet you could dunk it in your coffee, represents what I think is the genre of erasures done right. Ruefle takes the base work, a mysteriously arbitrary book from the 19th Century, and with her WhiteOut pen in hand, breathes a haunting life into each tight page. "A Little White Shadow" (also the title of the erased work) is enchanting visually, with its antiquey type face, tea-stained parchment, and textured streaks of WhiteOut, which appropriately cast their own shadows down each page, leaving only a few careful words. The paper alone, with all its high production value, counts for a lot of the specialness and intimacy of the erasures. I experience Ruefle's book like a piece of visual art almost as much as I do a collection of poems. A pocket-sized feast for the senses.The reader can't make out the work's original text at all, which gives "A Little White Shadow" an unapologetic vibrancy and sense of emotional purpose. The pages, though pretty, are sparse, with no titles, and sometimes less than a dozen visible words. This petite, pared-down style gives the poems a haunting wistfulness. In one poem, everything on the page is shadowed-out, save for a few small words scattered throughout the last three lines:

It

was my duty to keep

the piano filled with roses.

Simple, direct, and ghostly erasures like this pervade Ruefle's tiny tome. By creating long shadows of white space on the page, she makes excellent use of the erasure format in order to create suspense. Forcing the reader's gaze to fall down the entire height of a page to reach a poem's completion contributes to the eeriness and tension. The book's reoccurring unnamed character of "she" has a similar enigmatic effect. By the time you arrive at the final page of "A Little White Shadow," it sort of feels as if you've just read an old, quixotic book of a stranger's secrets. Personally, I have respect for any poet who can make me feel such an emotion, regardless of whether her pen was filled with ink or WhiteOut.So, in the few weeks left until West 10th's next issue is released, if you're feeling bored and restless with nothing to read, you might rediscover Mary Ruefle's "A Little White Shadow." This teeny book may not keep you busy until April, but it can at least get you out of the snow for a while.