It was July when Merriam first spoke properly to Susanne Lewis.

The girl sat on a stool beside her, wearing a baby-blue A-line skirt that some of the girls often wore to church, the ones with the puffy sleeves. They sought refuge from the sun on the balcony of the house, the air smelling of heat and the damn-near burning wood of the patio. Merriam had made some lemonade when it became obvious Susanne had no intention of soon leaving. Susanne didn’t so much as glance at the pitcher.

“You read a lot, don’t you?” Susanne asks abruptly. When she sees the confused look Merriam sends her, the girl elaborates: “I saw your bookshelves inside. They didn’t seem like nothing Mr. Anderson would read, and you don’t have kids, so… I figured they’re yours.”

Merriam hesitates. Her fingers drum on her thigh, and her breathing goes shallow. “They are.”

“You went to school, too, didn’t you? One of the nice ones. Out of state.”

“I did.”

“I bet it’s because you read a lot. That’s what everyone says, right? You get smart reading. That’s what my mama told me. I was never good at reading. Only thing I ever read was the Bible, and then I got tired of that.”

“The Bible isn’t something you tire of reading,” Merriam says.

“Yeah. Well, I did. I got bored. It’s boring.” Susanne stares at Merriam, as if daring her to object. “The only stories I liked were the love stories,” Susanne says. “But I never read them myself. My mama read them to me, instead. When I was little. The ones with the princes and grand weddings. The happy ones, though, not the sad ones. I didn’t like the sad ones.”

Merriam suspected Susanne had an exceedingly shallow understanding of the word like.

“But then you get married, and it’s never really like that, is it?” Susanne muses. She stares at nothing, eyes glazed over as she strokes her chin. “All you hear married people do is complain about the other. They always say they’re joking, but everyone knows they’re not.”

Susanne’s brows furrow, and then she’s turning on the stool she’s perched on to look at Merriam.

“Have you ever had that, Mrs. Anderson? That kind of sweet love in the stories and songs?”

“No.”

“I think it’s possible. Maybe. I mean, it has to be, right? Where else would they have gotten the inspiration to write them in the first place?”

Merriam says nothing. She taps the ash off her cigarette instead, licking at her gums.

“The Flock has it, I think. Love,” Susanne murmurs. She traces the lines on her palm as she thinks. “I know you all don’t think we do, but we have it.” Susanne looks at Merriam. Merriam looks at Susanne. “The Flock could love you too, you know.”

“Don’t,” Merriam mutters. The last thing she needs is to join some hippie cult consisting of runaway teens and middle-aged burnouts. And even if Merriam has reached a point where she’s desperate enough to throw her life away in favor of wearing white linen religiously, it’s not to join a flock.

Merriam doesn’t want the love of a lamb. It’s too soft. Too delicate. She craves something with teeth to devour her whole and without scrutiny. Something that makes her feel better about her own rottenness. And maybe that’s why she ended up with Winston in the first place. Maybe she’s always known better. Maybe she likes how much better of a person she’ll always seem in-comparison with him.

“Were you and Winston ever in love?” Susanne asks. “Any kind at all?”

Merriam doesn’t look at her when she asks that. Susanne has those wide eyes, bambi-eyes, the kind that make someone’s skin crawl at the sudden awareness that comes with being perceived by something so innocent. Merriam can’t stand that feeling, can’t stand the expectant expression that comes with it. Susanne only asks questions that she already has a desired answer for, and Merriam fails to answer correctly every time.

“No,” Merriam says, finally. She goes quiet for a moment—sucks on her lipstick-stained teeth—and then she continues. “Winston doesn’t know how to love. Just obsess. And even then, that ain’t for anything living. Craving a bottle of whiskey is the closest he’s ever come to wanting for something, and that’s just for keeping the aches away.”

Merriam doesn’t include that she liked that about him when she first married him. Liked knowing he didn’t love her. Because then, it meant she didn’t have to love him, or even pretend to.

What she didn’t like, however, or even know about at the time, was his passion. The part of him that wasn’t detached. The part of him that asked to see his brother’s ruined face at a closed-casket funeral.

“Did you know that when you married him?” Susanne asks. “That he was like that?” Her voice comes out pinched. Tense. It makes Merriam’s spine straighten as she watches Addler’s Bakery close up for lunch across the street.

“I did. Not everything, but I knew.”

Hunger. That’s the best word for it. There’s a hunger in Winston. One he doesn’t know how to quell. Or maybe one he just doesn’t want to.

Merriam takes a drag from her cigarette, leaving a ring of Avon red on the filter. Her fingers pinch it like it’s something delicate, elegant, her crimson nail polish gleaming in the midday sun. Winston had his vices. She had hers. At least she could look decent while doing it.

“So why?” Susanne asks.

“Why what?”

“Why marry him? You could’ve gone anywhere. Done anything. You got out.”

Merriam snorts. She snorts, and she’s not even bothered to try and cover it up with the back of her hand or to look away demurely. Instead, her lips curl back in a self-repulsed sneer. How does she begin to explain it? How does she give an answer to Susanne that doesn’t make the girl find her repulsive? Merriam herself can’t even stare into a mirror herself without wanting to break it, and even that’s a poor replacement for what she truly wishes she could do to herself.

“You were married once,” Merriam says, avoiding the question entirely. Susanne blinks, and then her brows raise, and the corner of her lips twitch.

“How’d you know?”

Merriam says nothing. Instead, her concealer-caked eyes flicker down to where Susanne compulsively rubs circles near the knuckle of her ring finger, even in its bareness. Susanne stiffens, then stops.

“Did you know?” Merriam asks. “When you married him?”

“Did I know what?” Susanne snips. Merriam’s eyes narrow as she takes another inhale from her cigarette, the smoke tickling the back of her throat before she blows it out through the nose. Susanne pouts, crossing her arms stubbornly as she looks the other way. “Smoking’s bad for you, you know.”

“Father John smokes.” Merriam shrugs, and takes another drag. That makes Susanne shut up quickly. Merriam takes the chance to enjoy the sound of the buzzing cicadas in the brief silence—the wonderful quietness that comes when Winston is away.

“I didn’t have a choice,” Susanne whispers finally.

“Mm,” Merriam hums, and that’s that. Susanne fiddles with the fraying stitching on her dress, and the ice cubes in the lemonade shift in the sweltering heat. Even the Jackson’s dogs are quiet, too miserable to bark at their own shadows.

“You know, Father John says that men are just animals,” Susanne says, staring at the beasts where they hide in their rotted-wood houses. “He says that we’re just as hungry. Just as desperate. We just pretend not to be. He says that some people know better than others, though. The ones who embrace it.”

“Yeah? And who’s that.”

“People who take what they want. Do what they want.”

Merriam’s lips press together, and then they purse, like having tasted something sour.

“And who would that be?” Merriam repeats. “My Winston? Your husband?”

“I’m not married. But yes.”

“You were.” A pause. “So what does that make us, then?”

“It makes you a coward,” Susanne states simply. She stares at Merriam, unblinking, expressionless.

Merriam’s eyes narrow in response.

“But we were all cowards once,” Susanne adds. “That’s why he calls us The Flock. We enter unknowing and blind. But eventually, we come to see the truth. To lead our own path. And then, we become like Father. He’s not like us, you know—not one of us. He’s our Shepherd. He shows us the way. Shows us the truth we’re too blind to see.”

Merriam lets out a breath she didn’t realize she’s been holding, and finds she’s pinching her cigarette so tightly that the filter’s crushed. She snuffs it out on the ashtray on the balcony’s railing, watching the smoke die out slowly.

“You hear yourself when you speak, don’t you?” Merriam asks. “Are you too dense to be offended?”

“Father John says only a fool becomes offended at their own reflection. I know what my nature is. I welcome it with grace. But I’m not a lamb anymore, either, you know. Father John says I’ve graduated.” Susanne pauses, head tilting like a curious pet. “I think you could, too. Become something greater.”

Something cold grips Merriam’s gut at those words. You could too. She frowns, and starts picking at the nailpolish on her finger to busy herself. Susanne takes it as an invitation to keep talking:

“You’re pathetic, sitting there, letting that man do as he wishes to you. I’ve seen it, and Father John has, too. You’re not like them. Not weak. So why do you let him treat you like you are?”

“What would you have me do?” Merriam mutters. A wry smile crawls onto her face, a hoarse chuckle sneaking past her lips. “Kill him?”

Would it be so wrong to confess she’s thought about it?

Susanne’s right eye barely twitches, and then she wipes her nose with her thumb as she sniffs. “That’s what I did,” she says. Merriam blinks. “It’s not hard,” Susanne continues. “You think about it for a little while, afterwards, but it’s really not so bad. And you don’t even have carpet flooring. That was the worst part, you know, the cleaning.”

The corner of Merriam’s lift twitches upwards. Her shoulders tremble, her chest shakes, and something akin to a grimacing grin crawls onto her face. Susanne smiles, too, but it’s not the same.

“What?” Merriam asks. A laugh escapes her, and her cheeks hurt from how much of her teeth she bares. But Susanne doesn’t laugh with her. She just keeps on going.

“Plus, you live on Main Street,” Susanne says. “Everything’s closed up when it’s dark. No one would hear you if you’re quiet enough. And even if they did, you can lie. Everyone knows what happened to William. Would it be that odd if it happened again?”

“Don’t talk about William.”

“I’m simply saying, Mrs. Anderson, no one would wonder. No one would talk. Even if the truth came out, no one would blame you.” Susanne’s eyes flicker between hers, her expression unreadable. “Aren’t you tired of pretending to cower? You’re not surviving,” Susanne says, “you’re acting.”

Merriam’s lips part, but no words come out. They get jumbled up and caught in her throat instead, keeping her from taking in a full breath. “You’re insane,” Merriam croaks. “I would never—I could never—”

“If you won’t, he will.” Susanne whispers. She hesitates then, wets her lips, and then she’s reaching out to clasp one of Merriam’s hands in her own. “Trust me, Mrs. Anderson. I know.” She squeezes Merriam’s hand, leans in closer—close enough for Merriam to count the freckles on her still baby-cheeked face. “I know.”

But Merriam also knows: Winston’s no killer. He’s a scavenger. The vulture that comes after the fact to slice open carcasses and eat their innards, leaving hollow-shelled-bodies behind. He’s too cowardly to be the one to make the kill himself. Always has been.

Slowly, Merriam pries herself from Sussanne’s grip. The girl’s hands are sweaty from the summer heat, a hangnail scraping Merriam’s finger as she pulls free.

“You need to learn to keep that tongue of yours in line,” Merriam says. “Not everyone in this town will be so willing to listen to your tall tales and instigating. No one else will find these jokes of yours funny.”

“It’s not a joke.”

“I’m not going to kill my husband,” Merriam snips, seething. Susanne’s eyes widen like a child being told no for the first time, and then she’s looking away, hands wringing the fabric of her dress. The conversation ends there, quickly, like that. The bells of the Church would soon ring, and the congregation of The Flock would soon head up to the white building on the hill to hold hands and speak of things like inner peace and transformation. And while Winston would end up dead in a month’s time, Merriam really hadn’t lied.

She wasn’t the one to do it.

Written in 1913 but only published posthumously in 1971, Maurice was well ahead of its time in its nuanced depiction of a young man discovering and coming to terms with his sexuality. While Forster carefully examines the difficulties of identity and love, Maurice is ultimately founded on the belief that same-sex relationships have the capacity to be profound, beautiful and happy—a radical thesis for a novel written when men were still routinely arrested and imprisoned for having sex with other men.

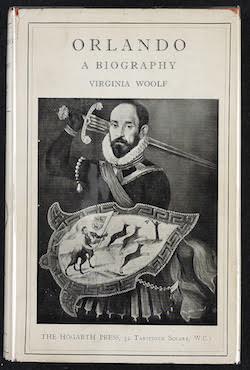

Written in 1913 but only published posthumously in 1971, Maurice was well ahead of its time in its nuanced depiction of a young man discovering and coming to terms with his sexuality. While Forster carefully examines the difficulties of identity and love, Maurice is ultimately founded on the belief that same-sex relationships have the capacity to be profound, beautiful and happy—a radical thesis for a novel written when men were still routinely arrested and imprisoned for having sex with other men.  Subtitled “A Biography,” Orlando was written as a paean to Woolf’s friend and erstwhile lover, the aristocratic Vita Sackville-West. With typical élan, Woolf transforms Sackville-West into the novel’s eponymous protagonist, a sex-changing immortal who begins as an Elizabethan nobleman and ends as a successful female author in ‘the present day’ (that is to say, 1928). Traversing three hundred years of Orlando’s life, Woolf relentlessly questions conventional notions of history, authorship, gender and sexuality. Nightwood - Djuna Barnes (1936)

Subtitled “A Biography,” Orlando was written as a paean to Woolf’s friend and erstwhile lover, the aristocratic Vita Sackville-West. With typical élan, Woolf transforms Sackville-West into the novel’s eponymous protagonist, a sex-changing immortal who begins as an Elizabethan nobleman and ends as a successful female author in ‘the present day’ (that is to say, 1928). Traversing three hundred years of Orlando’s life, Woolf relentlessly questions conventional notions of history, authorship, gender and sexuality. Nightwood - Djuna Barnes (1936) Contained in a deceptively slim volume, Nightwood is a superbly stylized portrait of a doomed lesbian relationship in the bohemian Paris of the interwar years, explicated through the head-spinning speeches of Dr. Matthew-Mighty-grain-of-salt-Dante-O'Conner (who is just as campy as his name suggests). This modernist masterpiece was lauded by T.S. Eliot as “so good a novel that only sensibilities trained on poetry can wholly appreciate it.” Notre Dame des Fleurs/Our Lady of the Flowers - Jean Genet (1943)

Contained in a deceptively slim volume, Nightwood is a superbly stylized portrait of a doomed lesbian relationship in the bohemian Paris of the interwar years, explicated through the head-spinning speeches of Dr. Matthew-Mighty-grain-of-salt-Dante-O'Conner (who is just as campy as his name suggests). This modernist masterpiece was lauded by T.S. Eliot as “so good a novel that only sensibilities trained on poetry can wholly appreciate it.” Notre Dame des Fleurs/Our Lady of the Flowers - Jean Genet (1943) Similarly to Nightwood, this novel renders the Parisian underworld in prose so rich and revelatory it practically creates a new class of literature. The lives and loves of its central characters—sex workers, trans women, and teenage murderers, all bearing charming monikers like Divine and Darling Daintyfoot—are unspooled by a capricious narrator who creates the world of the novel while masturbating in his prison cell (!!!). The Charioteer - Mary Renault (1953)Renault, having worked as nurse at a British military hospital during the Second World

Similarly to Nightwood, this novel renders the Parisian underworld in prose so rich and revelatory it practically creates a new class of literature. The lives and loves of its central characters—sex workers, trans women, and teenage murderers, all bearing charming monikers like Divine and Darling Daintyfoot—are unspooled by a capricious narrator who creates the world of the novel while masturbating in his prison cell (!!!). The Charioteer - Mary Renault (1953)Renault, having worked as nurse at a British military hospital during the Second World  War and later emigrated to South Africa to live with her female partner, was uniquely equipped to write this novel, which follows a British soldier who falls in love twice over as he recovers from a combat wound. With equal measures of heartfelt psychological insight and cutting social observation, The Charioteer struggles with the tensions between idealism and reality, individualism and community, and innocence and experience. Another Country - James Baldwin (1962)An earlier novel of Baldwin’s, Giovanni’s Room, is often hailed as a masterpiece of gay literature, but while Giovanni’s Room is a claustrophobic investigation of one man’s psychology, Another Country seems to encompass an era.

War and later emigrated to South Africa to live with her female partner, was uniquely equipped to write this novel, which follows a British soldier who falls in love twice over as he recovers from a combat wound. With equal measures of heartfelt psychological insight and cutting social observation, The Charioteer struggles with the tensions between idealism and reality, individualism and community, and innocence and experience. Another Country - James Baldwin (1962)An earlier novel of Baldwin’s, Giovanni’s Room, is often hailed as a masterpiece of gay literature, but while Giovanni’s Room is a claustrophobic investigation of one man’s psychology, Another Country seems to encompass an era.  The characters are gay, straight, bisexual, questioning and in denial; white and black; working-class and middle-class and destitute and wildly successful. In a rhythm reminiscent of jazz, the novel traces the cast as they move in and out of each other’s lives, coupling and splitting up and getting back together, rising and falling in fortune—but always circling around the specter of a character who commits suicide at the end of the novel’s first act.

The characters are gay, straight, bisexual, questioning and in denial; white and black; working-class and middle-class and destitute and wildly successful. In a rhythm reminiscent of jazz, the novel traces the cast as they move in and out of each other’s lives, coupling and splitting up and getting back together, rising and falling in fortune—but always circling around the specter of a character who commits suicide at the end of the novel’s first act.