Submission period over

Thanks to everyone who sent in submissions! We can't wait to review your work. You can expect to hear back from us in mid February.Have a good vacation!

Thanks to everyone who sent in submissions! We can't wait to review your work. You can expect to hear back from us in mid February.Have a good vacation!

We are extending the West 10th submission deadline until finals week is over, since we won't start reading submissions until that time. Please send your work to west10th.submisisons@gmail.com by DECEMBER 23. Good luck with finals, and we look forward to reading your submissions. More information can be found on our submissions page.

Today is the LAST DAY to submit poetry, prose, and art to West 10th! Get your submissions in by midnight to west10th.submissions@gmail.com

More information on our submissions page.

Don't forget to submit your poetry, prose, and art to the 2012-2013 edition of West 10th! The deadline is Sunday, December 16th. Read more about the submissions guidelines and download the submission form.All questions and submissions should be sent to west10th.submissions@gmail.com

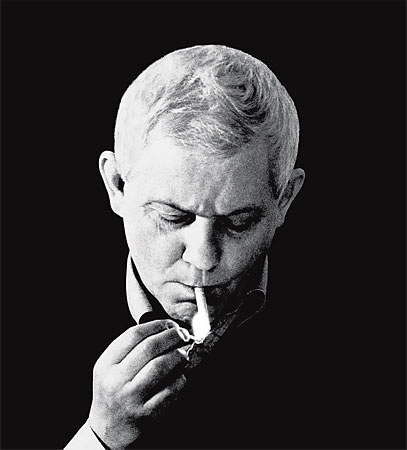

Polish poet Zbigniew Herbert (1924-1998) is perhaps best known in America for his poem “Report from the Besieged City,” and for his ability to demythologize time-worn tales as in “Why the Classics” or “Daedalus and Icarus.”In 1999 Ecco Press published Elegy for the Departure, a collection of poems translated into English for the first time. The collection includes poems from Herbert’s 1990 book of the same title as well as poems from earlier volumes. The book is arranged in roughly chronological order from 1950 to 1990. Some of the poems, especially in the first section, display Herbert’s attention to myth, his political voice: “—how to lead / people away from the ruins / how to lead / the chorus from poems—”. Much of the collection, though, turns to a more personal voice. He speaks often of his childhood: “home was the telescope of childhood / the skin of emotion / a sister’s cheek / branch of a tree.” In the later poems of the book he is ruminative, looking back upon his life: “I thought then / that before the deluge it was necessary / to save / one / thing / small / warm / faithful.” The language throughout the collection is lively, whimsical when you least expect it. Section three is made of clever prose poems that read like abbreviated fables: funny and sad all at once. Each is titled with a single noun, which the poem goes on to offer a definition of. “Drunkards” are people who “drink at one gulp, bottoms up,” who spend their time looking up through the necks of their bottles, but maybe “if they had stronger heads and more taste, they would be astronomers.” We also hear from a Wolf caught in one of Aesop’s fables. The wolf is terrorizing the sheep, but he admits that, “Were it not for Aesop, we would sit on our hind legs and gaze at the sunset. I like to do this very much.”I am continually amazed in reading Herbert’s poems—both long and short—at his ability to move the reader forward in the poem without any use of punctuation. This is a style that is certainly abused by many of us amateur writers so it is refreshing to see it done so well. I’ll leave you with my favorite lines from the book, which demonstrate the energy and rhythm of Herbert’s writing. From “The Troubles of a Little Creator”:A small puppy in vast empty spacein a world not yet readyI worked from the beginningwearing my arm to the quickthe earth uncertain as a dandelion puff ballI pressed it with my pilgrim’s footwith a double blow of my eyesI fixed the skyand with a mad fantasyimagined the color blue--Laura Stephenson, Editor-in-Chief

Polish poet Zbigniew Herbert (1924-1998) is perhaps best known in America for his poem “Report from the Besieged City,” and for his ability to demythologize time-worn tales as in “Why the Classics” or “Daedalus and Icarus.”In 1999 Ecco Press published Elegy for the Departure, a collection of poems translated into English for the first time. The collection includes poems from Herbert’s 1990 book of the same title as well as poems from earlier volumes. The book is arranged in roughly chronological order from 1950 to 1990. Some of the poems, especially in the first section, display Herbert’s attention to myth, his political voice: “—how to lead / people away from the ruins / how to lead / the chorus from poems—”. Much of the collection, though, turns to a more personal voice. He speaks often of his childhood: “home was the telescope of childhood / the skin of emotion / a sister’s cheek / branch of a tree.” In the later poems of the book he is ruminative, looking back upon his life: “I thought then / that before the deluge it was necessary / to save / one / thing / small / warm / faithful.” The language throughout the collection is lively, whimsical when you least expect it. Section three is made of clever prose poems that read like abbreviated fables: funny and sad all at once. Each is titled with a single noun, which the poem goes on to offer a definition of. “Drunkards” are people who “drink at one gulp, bottoms up,” who spend their time looking up through the necks of their bottles, but maybe “if they had stronger heads and more taste, they would be astronomers.” We also hear from a Wolf caught in one of Aesop’s fables. The wolf is terrorizing the sheep, but he admits that, “Were it not for Aesop, we would sit on our hind legs and gaze at the sunset. I like to do this very much.”I am continually amazed in reading Herbert’s poems—both long and short—at his ability to move the reader forward in the poem without any use of punctuation. This is a style that is certainly abused by many of us amateur writers so it is refreshing to see it done so well. I’ll leave you with my favorite lines from the book, which demonstrate the energy and rhythm of Herbert’s writing. From “The Troubles of a Little Creator”:A small puppy in vast empty spacein a world not yet readyI worked from the beginningwearing my arm to the quickthe earth uncertain as a dandelion puff ballI pressed it with my pilgrim’s footwith a double blow of my eyesI fixed the skyand with a mad fantasyimagined the color blue--Laura Stephenson, Editor-in-Chief

Hello friend. How are you? It’s been a long time. It’s been over a year since I last assigned you a book to read. Did you manage to power through that 192-page book in the 388 days it has been since I last spoke to you? I hope so. I didn’t want come back too soon and spook you off. I just want you to be comfortable.For those of you who were able to finish Civilwarland in Bad Decline, I have another recommendation. For the rest of you who need another 388 days, take your time. I’ll check back with you on December 2, 2013.Swimming to Cambodia is a book by a fella named Spalding Gray. He was asked to play a role in the The Killing Fields, a film about the Cambodian Civil War. Swimming to Cambodia juxtaposes his adventures and shenanigans while filming a Hollywood movie against the real story and history of the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia, and the result is simultaneously gut busting and gut wrenching.I bet you’re asking yourself “Hey Conor, I get why you’d recommend this to a smarty-pants who likes books, but why would you recommend it to somebody who doesn’t like to read?” I’ve got three major selling points for you my friend.It’s funny. Spalding Gray has a mastered a sort of dirty neuroticism that reminds me of the hypothetical baby-fusion of Woody Allen, Harmony Korine, and Hunter Thompson. A decent-sized portion of this book deals with Gray, a neurotic and gawky man in his 40’s, trying to conquer his fear of the ocean while high on opiates. It is exactly as good as it sounds.It’s short. The edition I’m holding in my hand is a scant 133 pages, and when you take into account how large the type and how small the pages are, the final page count becomes even less intimidating. I managed to plow through this in two hours while waiting for a train home before Hurricane Sandy.It’s smart. The parts of Swimming to Cambodia that aren’t dealing with a man stoned out of his gourd coping with his hydrophobia are extraordinarily insightful and powerful. If you were to ask me before this book what the Khmer Rouge was, I probably would’ve responded “A video game character.” Though the subject matter is often lighthearted, Gray is capable of switching gears instantaneously. The story takes wild nosedives that leave you at the precipice of despair, before Gray finally pulls up on the controls and resumes talking about wanting to marry a hooker.Look. I’m not a dummy. I know how these things work. I assign this book to you, and you just sit around on reddit procrastinating until 2 AM, when you panic, realize you won’t be able to read the book, and desperately scramble to look for a movie version. Then you leaf through Google and Sparknotes, hoping to find somebody who has made a list of the differences between the film and the book, so that you can come back to me appearing as prepared as possible.Rest easy my friend: I’ve got you covered. Swimming to Cambodia was originally written as a monologue. It was designed from the get-go to be watched.

"He broke it all down to a table, a glass of water, a spiral notebook and a mic. Poor theatre—a man and an audience and a story. Spalding sitting at that table, speaking into the mic, calling forth the script of his life from his memory and those notebooks. A simple ritual: part news report, part confessional, part American raconteur. One man piecing his life back together, one memory, one true thing at a time. Like all genius things, it was a simple idea turned on its axis to become absolutely fresh and radical."

-Theatre Director Mark Russell on Spalding Gray

Jonathan Demme, the man who directed Silence of the Lambs and Philadelphia adapted Swimming to Cambodia for the screen. However, this is not a scenario in which you’d have to scramble around the Internet trying to find out any differences between the book and the film. I’ll make this easy for you: there are none. The exact same thing you see on screen is right there in your book.Now, don’t get me wrong: I’m not necessarily suggesting that you only go and watch the film. There are a few things that might go over your head if you’re not paying full attention, and it definitely helps to be able to flip back. By no means am I saying that this book will make you feel dumb, but as it deals with Cambodia, a place I’m assuming you’re not familiar with, sometimes the names and other proper nouns can get confusing. It’s not a particularly difficult book, but it will definitely keep you on your toes.I’ve saved my trump card for last. If I haven’t won you over yet, listen up. There’s a story in the book about John Malkovich telling a dirty joke. So, get on that man.-Conor Burnett, Prose Editor

"Every so often, that dead dog dreams me up again." And we're there, at attention. A bravura opening line, full of pulls, secrets. I get chills reading it. That dead dog dreams me up. We're going back in time, we're going to experience everything after that line in a backwards frame dreamed up by a dog. He won't be the narrator, though - just the spirit guide, if you will.

That's not the opening line of this collection of short stories, originally published in the early 1990s and recently re-released by Other Press. But it is the single sentence that best captures Stephanie Vaughn's astonishing, Grace Paley-like facility with the technical construction of the short story, and with the artistic achievement possible when a novel's worth of emotions and relationships are compressed into brilliant, diamond-like stories. It also shows how she does it without showing off. No big words, no strained punctuation. None of the flailing that all of us, the lesser talents, have to resort to.

Many of the stories are about the often-unwritten world of children growing up on military bases - four of the stories, including "Dog Heaven," from which the opening quote is taken, are narrated by Gemma; whose father works for the US Army and who travels with him around the country as he takes new posts. The transience of these lives, their brief connections, the way these children are planted and ripped out until they grow thick emotional calluses, are brilliantly explored.

For the last few months, I've been traveling - I'm currently studying in Berlin, and over the summer I worked in western Massachusetts. This is the book that I've brought with me, wherever I go.

-Ben Miller, Assistant Prose Editor

-----

An Excerpt from "Able, Baker, Charlie, Dog," from Sweet Talk, by Stephanie Vaughn. Copyright 2012, by Stephanie Vaughn. Sweet Talk is in print and available from Other Press.

I went downstairs and put on my hat, coat, boots. I followed his footsteps in the snow, down the front walk, and across the road to the riverbank. He did not seem surprised to see me next to him. We stood side by side, hands in our pockets, breathing frost into the air. The river was filled from shore to shore with white heaps of ice, which cast blue shadows in the moonlight.

“This is the edge of America,” he said, in a tone that seemed to answer a question I had just asked. There was a creak and crunch of ice as two floes below us scraped each other and jammed against the bank.

“You knew all week, didn’t you? Your mother and your grandmother didn’t know, but I knew that you could be counted on to know.”

I hadn’t known until just then, but I guessed the unspeakable thing—that his career was falling apart—and I knew. I nodded. Years later, my mother told me what she had learned about the incident, not from him but from another Army wife. He had called a general a son of a bitch. That was all. I never knew was the issue was or whether he had been right or wrong. Whether the defense of the United States of America had been at stake, or merely the pot in a card game. I didn’t even know whether he had called the general a son of a bitch to his face or simply been overheard in an unguarded moment. I only knew that he had been given a 7 instead of a 9 on his Efficiency Report and then passed over for promotion. But that night I nodded, not knowing the cause but knowing the consequences, as we stood on the riverbank above the moonlit ice. “I am looking at that thin beautiful line of Canada,” he said. “I think I will go for a walk.”

“No,” I said. I said it again. “No.” I wanted to remember later that I had told him not to go.

“How long do you think it would take to go over and back?” he said.

“Two hours.”

He rocked back and forth in his boots, looked up at the moon, then down at the river. I did not say anything.

He started down the bank, sideways, taking long, graceful sliding steps, which threw little puffs of snow in the air. He took his hands from his pockets and hopped from the bank to the ice. He tested his weight against the weight of the ice, flexing his knees. I watched him walk a few years from the shore and then I saw him rise in the air, his long legs, scissoring the moonlight, as he crossed from the edge of one floe to the next. He turned and waved to me, one hand making a slow arc.

I could have said anything. I could have said “Come back” or “I love you.” Instead, I called after him, “Be sure and write!” The last thing I heard, long after I had lost sight of him far out on the river, was the sound of his laugh splitting the cold air.

The editors of West 10th invite you to a poetry workshop on Tuesday, November 13th at 7pm in Bobst LL2-07. Please bring one poem of up to 3 pages or a prose poem of under 500 words for the group to read and discuss. You may also bring brief excerpts of fiction.This is West 10th's first time hosting a community-wide workshop, a great opportunity for NYU undergrads to polish up on a piece of their writing. Also, a chance for us editors to get to know you!Refreshments will be served. We look forward to reading your work! For more information please visit the facebook event page. RSVPs are appreciated.Additionally, we would like to announce that the submission deadline for West 10th has been pushed back to Sunday, December 16th. In light of the recent hurricane and subsequent rushed academic schedules, we want to give you some extra time to work on submissions. Please check out submissions page for guidelines before submitting.

In my experience, the Dickman brothers and their poetry are polarizing topics amongst creative writers. Most people really do either love or hate them. I’ll admit that I was in the latter camp, – I was suspicious of the Dickman public image, which is very Portland, cool and offbeat, and this prejudice ruined what individual pieces of theirs I read or heard read aloud – until, like a critic should, I gave their work a fair chance. When I actually read Matthew and Michaels’ poetry collections in full, I flipped.Flies won me over to Michael Dickman. Mayakovsky’s Revolver similarly convinced me of Matthew. The collection, which West 10th reviewed earlier this month, is full of surprising language and metaphor. My favorite example occurs in The Gas Station, when Matthew encounters a gunman: “this guy came out swinging / a gun, his face like an apartment / that no one had lived in for years, / the gun pointing just above my head when it went off, …”Due to its thematic content, Matthew’s collection may not be entirely accessible on the whole. Not every reader has been threatened with a firearm. Neither have most readers lost a sibling to suicide, a narrative that runs throughout Mayakovsky’s Revolver. Regardless of how foreign some of the collection’s content may be, most of its poems are believable and engaging.This is due to the fact that the emotion behind the language feels honest. Before Mayakovsky’s Revolver, I’d unfairly assumed that Dickman’s poetry relied more on gimmick than on art and was more striking for its cool, modern voice than for its sincerity. Mayakovsky’s Revolver, for the most part, proves both assumptions wrong. The collection is consistently both artful and passionate.Only one piece, entitled Dark, made me think that perhaps my original misgivings about Dickman’s poetry, which are doubts that a lot of haters share, carried some weight. Dark occurs in Mayakovsky’s Revolver’s second section, Elegy to a Goldfish. In general, I am less enamored of this section than of the rest of the book. But, I have a definite issue with the piece Dark.Dark includes bits of different stories – a line about an abused boy, a line about a self-abusive girl – in an arc that focuses mainly on Dickman himself. Neither the story of the abused boy nor of the self-abusive girl is developed; neither the boy nor the girl is even named. These two characters feel inauthentic, like archetypes of other people that appear in the collection; the inclusion of their stories feels gratuitous. In Mayakovsky’s Revolver, Dark presents a disappointment. It lacks cohesiveness and, I think, the emotional urgency that makes the rest of the collection so compelling.--Lauren Roberts, Managing Editor

Robin Sloan’s debut novel, Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore, takes a formula for classic intrigue and updates it for a 21st Century audience. Clay Jannon, a recent college graduate, falls victim to the Recession of 2008 and loses his web design job when the company he works for goes under. Out of necessity, he takes a job at the titular Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour secondhand bookstore. However, he soon discovers that the majority of Mr. Penumbra’s customers are part of a mysterious club, which borrows one-of-a-kind volumes seemingly filled with gibberish, and that Mr. Penumbra’s bookstore is not the only one of its kind.

But, Sloan’s novel is more than just a compelling narrative; his juxtaposition of analog and digital books cleverly explores the ways in which we have fully integrated technology into our literary lives without sounding overly pedantic. Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore manages to be both fun and insightful, and a truly modern mystery.

-Rebecca Rae, Copyeditor

In Beauty Bright, Gerald Stern’s latest collection of poems, is meditative, celebratory, intimately sad, and funny. Stern deals in terms of time, gathering up old years and sticking them in with new ones. Midway through a poem that seems to be taking place in the present, he’ll admit: “it is probably / April and it’s probably twenty, thirty / years ago” and then he’ll move along, keeping the focused, wild momentum that is so familiar in his writing. The span—temporal, geographical, tonal—of a Stern poem is immense. He moves from the Ruhr to New Jersey to the Mississippi; from 1936 to the American Revolution; from violence to a place where “everyone hugged / the person to his right although the left was / not out of the question”. He sorts through his personal past in the same lines that he grapples with the pasts of entire cultures and countries.Stern is 87 now, and has written seventeen collections of poetry. He writes about his age often—“for I am going in reverse / and my slow mind has ruined me”; “Too late now to look for houses / to give readings, to flirt, to eat blueberries / to dance the polka”—but he is also preoccupied with the fullness of things that have already happened. He recalls streets and people in clipped and intense detail, occasionally confessing “I don’t know what the year was” or musing “someone should mark / the day, I think it was August 20th”. The poems of In Beauty Bright are rich and strange, and they barrel forward with a strong, intuitive rhythm. Stern himself is as observant and expansive as ever, naming what used to be around him with the same care as he names what’s still around, proclaiming “there is so much to say about him I want to / live again,” granting each small thing and year its due attention.--Maeve Nolan, Poetry Editor

Sifting through second-hand paperbacks at a musty bookstore on the Upper West Side I stumbled upon Das Energi, a hippie-spiritual classic from 1974 that I’d heard my friend’s parents talk about when they would reminiscence about times when music was political and LSD was legal. It was one of those popular books that everyone eventually forgot about as the decade passed and the peace and love mentality of that generation faded into the 80s.Usually these kinds of “Feel the world, heal the world” narratives can be hard to get through, mostly because they are repetitive and almost always vague, but this one struck a somewhat different note. Paul Williams manages to weave lyrical prose with hard slang into a strong and thoughtfully structured manifesto, a mantra for a new way of living life. The structure of Das Energi follows suit, each page as varied as the voice. Some pages are run-on paragraphs, set in a conversational tone Williams asks an obscure “you” why fear is so potent, why we choose to ignore the metaphysical implications of our existence. Others are only a line, something short and thoughtful to be repeated over and over again. Though he traverses a number of topics, from guiltless sex to our obsession with efficiency to the potency of religion, the one line he refers back to constantly is: “You are God”. Williams seems to believe that worshipping a separate and nonhuman entity is pointless and detracts from the self-evolution and discovery that is necessary to contribute to the energy flow of the world.In some ways Williams came very close to sounding like the stoned middle-aged gypsies you might bump into at Burning Man while waiting in line for beer, but it is his stylistic voice that separates him from the ‘wishy washy’ aspects of spiritual culture that mainstream society can’t seem to handle. He has a very forceful approach to his doctrine and often ends up sounding much more like Karl Marx than Gandhi. His constant reference to “shedding old skin”, “setting yourself free” and of “not seeking but finding” are dispersed between urgent didactic lines like “Here and now, boys. Or else spend infinite future fighting quarrels of endless past.” He pushes forward the importance of responsibility and even outlines three self-made laws of the economics of energy. Admittedly Williams’ inconsistency in writing is sometimes shaky—it is harder to sink into a piece that chooses not to commit to any tone or mood—but he is nevertheless an earnest and often charismatic writer with enough skill to pull off a book that could have been excruciating. His words are familiar the way an old jazz tune at a coffee store is; you know the basic melody but the vocal riffs and trumpet solo always take you buy surprise.--Michelle Ling, Art Editor

Elaine Equi's newest collection, Click and Clone, is a clever, playful exploration of "the tone and timbre of American life as it has been colored by the new metaphors and images brought to us by our continuing technological revolution." Equi's poems are punchy and energetic yet intimate, and she displays a surprising breadth of form. From faux tarot readings to a sonnet comprised entirely of headlines written by consummate poets at the New York Post, Equi strives to overthrow the common and the fixed. In "Follow Me," she declares, "I don't stay / inside the line. / I don't go / outside the line. / I am the line itself."Whether writing about clones or consumerism or Haruki Murakami, Equi shamelessly exhibits her wit with wordplay and poignant aphorisms. Yet there are times when Equi crosses the line between clever and banal, when it seems like she tries too hard to elicit a few laughs. For the most part, however, she remains as fresh and modern as the title of the collection itself.Click and Clone is not for the timid or the steadfastly old-fashioned. As Equi puts it in "Side Effects May Include," "Warning: these poems may cause / headaches, hives, hard-ons in women, / . . . Do not read these poems if you are pregnant / or nursing without consulting a doctor first."--Jarry Lee, Assistant Poetry Editor

Percussion Grenade (Fence Books, 2012), Joyelle McSweeney’s third full-length poetry collection, begins not with an explosion, but with a warning: she intends for her poetry to be read aloud. She likens you to a Looney Tune and to a flight attendant. This is the first page.The three that follow, however, are a waste, as are many throughout the book—blotted with Douglas Kearney’s illustrations. Kearney depicts the title images and obvious themes of the book’s sections. These depictions, however, are purely literal and lack an interesting perspective. They subtract from the otherwise extraordinarily dense block of text that is Percussion Grenade.Like fragmentation, McSweeney’s poetry violently rips through every thought that falls within its “killzone.” This killzone, however, is not grenade-sized. Her work is an atomic bomb. The thoughts are all but neutralized.And she’ll beat anything to death. Each poem relies on dozens, sometimes hundreds, of images. They appear, they reappear, they disappear—they are flung at the page from every direction. Consistency isn’t worthy of her writing. It speaks—or screams, rather—for itself:

Crescendo! MacCaw! I’m a magpie with a caralarm and an airplane a patented / genome a reinforced cockpit door and a poptab brain a vivisected aquifer / shunted and split ten ways between here and the San Fernando Valley and the / Rift valley and the Kusk Valley the Rhine and Tuscaloosa and South Bend and / St Marks Venice and St Marks / Opeeeeeeeeogalala! OpeeOrkneyIslanders! BushTwins! OpeeeeeeeeCree!

“Opeeeeeeeentropy!” Percussion Grenade is an unleashing of poetic chaos, literary terrorism. She warned us.-Beau Peregoy, Poetry Editor

Recently, I read a wonderful collection of short stories by Kij Johnson called "At the Mouth of the River of Bees". In this book, no two stories are the same. Each one is separated by the immeasurable leaps of Johnson's imagination and her unbridled creative energy. As I progressed through the book, I encountered a slew of different fantasies: a magic act consisting of 26 monkeys, a claw-foot bathtub, and a magician that doesn't understand her own tricks; a nomadic tribe of horse raiders that wander a distant planet in search of a cure for a plague that has devastated their horse population; a glimpse inside the impossible "Schrödinger's Cathouse", where the drinks flow, the women simmer, and nothing makes sense because quantum mechanics suck and there is really nothing we can do about that; and a scene of mind-blowingly explicit intercourse between a young woman and an alien that left me feeling more violated than when the girl who sat behind me in my 5th grade math class insisted on whispering profoundly erotic phrases in my ear while we practiced long division.No, that isn't a euphemism. No, I didn't think it sounded like one, but you can never be too sure anymore.Either way, this is just the tip of the narrative iceberg. The book is a sincere testament to what stories are capable in terms of both content and style. And yet for all of the science fiction and fantasy elements present, Johnson's most impressive achievement is her lyrical examination of the human spirit and the finely woven threads of horror and beauty that run through even our most simple moments.The best example of this lies, in my opinion, in the story from which the collection takes its name. Without giving too much away, "At the Mouth of the River of Bees" follows the story of Linna and her very ill dog, Sam, as they travel along the banks of a river of bees that has mysteriously appeared across the state of Montana. What is remarkable about this story is not the massive stream of bees rampaging across Montana, but the depth of feeling between Linna and Sam. Linna is aware that Sam's days are numbered, but she still insists on sticking to their routines, and he, perhaps out of loyalty, continues to plod along beside her, concealing his pain the whole time.But there is a moment in the story when the routines fall away and Linna has no choice but to face the reality of the inevitable. It is dark, and Linna decides to park her car so Sam can rest. She watches him while he sleeps. He's just lying there, splayed out in the backseat, his chest rising and falling in the faint starlight that presses against the windowpane, and it seems as though death's infinite arms are creeping closer and closer to her companion. Her thoughts scream "live forever", but all we hear is the thundering procession of bees outside the car.This is the masterstroke of Johnson's work. For it was in this moment that I found my foundation in a veritable river of bees. For me, this absurdity was the only source of comfort I could experience. In contrast, this dying dog appeared unsettling in his strangeness and his beauty, and I felt the need to embrace him mingle with the most basic, indescribable terror. There are many moments in the book when, through a juxtaposition of the fantastic and the real, Johnson restores the magic back to real life, that which should always be miraculous to us, even if on the most fundamental level.--Joe Masco, assistant poetry editor

The brothers Dickman, Matthew and Michael, found themselves thrust face-first into the world of poetry around 2009, when both had recently published their first full collections of poems from Copper Canyon Press. The two received mixed reactions to their collective worth, heralded as either a gimmick of hip, Portland poets, or as a sort of polarized harmony, where each poet’s distinctly different style pulled away from his twin’s, only to have each void filled with the other brother’s voice.With his newest collection, Mayakovsky’s Revolver, Matthew Dickman has established himself independent of any of the gimmicks or cheap tricks. Mayakovsky’s Revolver is drenched in a sort of dark enlightenment, a world permeated with imagery that is at once visceral and hauntingly surreal. This is a world where the speaker’s third grade teacher wears “a rosary of barbed wire underneath her white blouse,” a world where the speaker will try to pass notes to his dead brother on the day of his funeral, filled with an entire penumbra of emotion.Dickman is still jubilant, but he is also quiet, pensive. The elements and subjects of the collection are at once celebrated and mourned, as “blackberries will make the mouth of an eight-year-old look like he’s a ghost.” The poems in Mayakovsky’s Revolver take place in quiet moments, the shadows of memories that can only exist in the world of poetry. The collection laments the death of a dead brother, while embracing the life of a twin brother, staring right into the smallest of moments, and, in spite of everything, managing to find great love and great loss.--Eric Stiefel, Assistant Poetry Editor

Last Friday, sixty or so noir-clad poetry bugs gathered in the Lillian Vernon Creative Writers House to hear two poets read. The first was Dorothea Lasky, a bundle of whimsy with an MFA in Poetry from UMass Amherst and a head of distinctly Dr. Seussean curls. The other was Eileen Myles, an ageless wordsmith from Boston, author of countless poetry collections and possibly one of the coolest people this side of the Mason Dixon. Both poets presented an assortment of new poems and also read from their most recent books, Thunderbird by Lasky and Snowflake/different streets by Myles.I attended this reading with the intention of writing a more standard review of each collection, but upon Ms. Lasky first opening her mauve-stained lips, I knew that the reading called for a different kind of commentary.Reading a book of poems alone, silently, is how we most often receive poetry. We take note of the visual clues on the page that help to guide our rhythm and perception of the work; but ultimately, the poems enter our brains via this strange portal where how the words look truly affects how they sound, and finally what they mean, more than any other type of writing. It doesn't always happen that the way you imagine a poem to sound will be how the poet actually presents it; and this surely didn't happen last night. I was impressed that both Lasky's and Myles's poems became brand new, and I think better, thanks to each of their extremely different, equally evocative "poem voices."Dorothea Lasky has a speaking voice that is so high-pitched and clear, it seems as if she never smoked or cursed a day in her life (though, as of Friday night, I can attest to the fact that at least 50% of that is highly false... see pg. 4 of Thunderbird). She is giggly and self-deprecating, making quips between poems to get the audience as comfortable as she seems to be. The voice she assumes once she starts reading possesses the same high-pitched, almost child-like quality, but suddenly increases in volume by 10 fold. Then most notably, her inflection takes on an alarming pattern where it sort of sounds like a 4th grader reading a paragraph about the solar system out loud to the class. Hearing this voice read lines like "I care for monsters/But only because I am one" and similarly simple and hard-hitting lines that riddle Thunderbird, changes the work. Lines that initially may appear dramatic or angry on the page, take on humility and occasional irony. At first listen, Lasky's "poem voice" was so different from what I expected that I found it a bit jarring. A few poems in, however, I wanted to immediately re-read her book, this time with an ear for how endearing and unique Thunderbird can sound.Below is a link to Lasky reading a poem from her book called Who To Tell. I recommend reading the poem silently and then having a listen.http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_F4_42iMQ-kJuxtapose Lasky's high-pitched, performative "poem voice" with Myles's gravelly, colloquial one for a mesmerizing study on how different poets choose to present their work. I attended a reading of Eileen Myles's over the summer where she revealed that she often writes poems in her head while driving; so, her process of putting the poem on the page is sort of a backwards translation from aural to visual. I can't speak for Lasky, but for Myles, how the poem sounds is a huge part of the equation. This becomes very clear when she reads.Myles's husky and understated speaking voice establishes upon first listen that this ain't her first West Village rodeo. She reads her poems breezily and conversationally; you can tell she's used to interacting with her poems off the page. She also reads quite quickly, but with such a cool self-assuredness, that even if her words flew by too fast for you to catch them, you find yourself nodding in comprehension. Most distinctly, as Myles reads poem after poem, a strong Boston accent surfaces, which is uncharacteristic of her every day speaking voice. This is not intentional, she admits. The accent slips in and grows thicker as she gets deeper into the experience of reading. This unique addition to her already colloquial voice gives simple lines like "For the most compelling birthday party I'd been to in a while I bought three cards," a jolt of charm, due to how those "ar" sounds so patently feature the Boston accent.Here is a video of Eileen Myles reading from Snowflake/different streets. See if you can detect all the awesome qualities of her "poem voice," and how they add to your experience of the work.http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dV5bnSCcewMThis wasn't the case on Friday, but I have certainly heard and been disappointed by writers that read work, which I loved on the page, aloud to an audience (an example would be Augusten Burroughs... sad). Not all experiences with "poem voices" at a reading will end well. But the role of the "poem voice" does add a fascinating element to the medium, putting poetry at a crossroads between a visual art, a literary art, and a performing art.Below is a link to the schedule of events at the Writers House this year. Free readings, free wine, free food for thought.http://cwp.fas.nyu.edu/page/readingseriesBy: Amanda Montell, Assistant Poetry Editor

Last Friday, sixty or so noir-clad poetry bugs gathered in the Lillian Vernon Creative Writers House to hear two poets read. The first was Dorothea Lasky, a bundle of whimsy with an MFA in Poetry from UMass Amherst and a head of distinctly Dr. Seussean curls. The other was Eileen Myles, an ageless wordsmith from Boston, author of countless poetry collections and possibly one of the coolest people this side of the Mason Dixon. Both poets presented an assortment of new poems and also read from their most recent books, Thunderbird by Lasky and Snowflake/different streets by Myles.I attended this reading with the intention of writing a more standard review of each collection, but upon Ms. Lasky first opening her mauve-stained lips, I knew that the reading called for a different kind of commentary.Reading a book of poems alone, silently, is how we most often receive poetry. We take note of the visual clues on the page that help to guide our rhythm and perception of the work; but ultimately, the poems enter our brains via this strange portal where how the words look truly affects how they sound, and finally what they mean, more than any other type of writing. It doesn't always happen that the way you imagine a poem to sound will be how the poet actually presents it; and this surely didn't happen last night. I was impressed that both Lasky's and Myles's poems became brand new, and I think better, thanks to each of their extremely different, equally evocative "poem voices."Dorothea Lasky has a speaking voice that is so high-pitched and clear, it seems as if she never smoked or cursed a day in her life (though, as of Friday night, I can attest to the fact that at least 50% of that is highly false... see pg. 4 of Thunderbird). She is giggly and self-deprecating, making quips between poems to get the audience as comfortable as she seems to be. The voice she assumes once she starts reading possesses the same high-pitched, almost child-like quality, but suddenly increases in volume by 10 fold. Then most notably, her inflection takes on an alarming pattern where it sort of sounds like a 4th grader reading a paragraph about the solar system out loud to the class. Hearing this voice read lines like "I care for monsters/But only because I am one" and similarly simple and hard-hitting lines that riddle Thunderbird, changes the work. Lines that initially may appear dramatic or angry on the page, take on humility and occasional irony. At first listen, Lasky's "poem voice" was so different from what I expected that I found it a bit jarring. A few poems in, however, I wanted to immediately re-read her book, this time with an ear for how endearing and unique Thunderbird can sound.Below is a link to Lasky reading a poem from her book called Who To Tell. I recommend reading the poem silently and then having a listen.http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_F4_42iMQ-kJuxtapose Lasky's high-pitched, performative "poem voice" with Myles's gravelly, colloquial one for a mesmerizing study on how different poets choose to present their work. I attended a reading of Eileen Myles's over the summer where she revealed that she often writes poems in her head while driving; so, her process of putting the poem on the page is sort of a backwards translation from aural to visual. I can't speak for Lasky, but for Myles, how the poem sounds is a huge part of the equation. This becomes very clear when she reads.Myles's husky and understated speaking voice establishes upon first listen that this ain't her first West Village rodeo. She reads her poems breezily and conversationally; you can tell she's used to interacting with her poems off the page. She also reads quite quickly, but with such a cool self-assuredness, that even if her words flew by too fast for you to catch them, you find yourself nodding in comprehension. Most distinctly, as Myles reads poem after poem, a strong Boston accent surfaces, which is uncharacteristic of her every day speaking voice. This is not intentional, she admits. The accent slips in and grows thicker as she gets deeper into the experience of reading. This unique addition to her already colloquial voice gives simple lines like "For the most compelling birthday party I'd been to in a while I bought three cards," a jolt of charm, due to how those "ar" sounds so patently feature the Boston accent.Here is a video of Eileen Myles reading from Snowflake/different streets. See if you can detect all the awesome qualities of her "poem voice," and how they add to your experience of the work.http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dV5bnSCcewMThis wasn't the case on Friday, but I have certainly heard and been disappointed by writers that read work, which I loved on the page, aloud to an audience (an example would be Augusten Burroughs... sad). Not all experiences with "poem voices" at a reading will end well. But the role of the "poem voice" does add a fascinating element to the medium, putting poetry at a crossroads between a visual art, a literary art, and a performing art.Below is a link to the schedule of events at the Writers House this year. Free readings, free wine, free food for thought.http://cwp.fas.nyu.edu/page/readingseriesBy: Amanda Montell, Assistant Poetry Editor

West 10th is now accepting submissions for the 2012-2013 edition! All submissions are due by the end of the day on November 30th. You may submit up to 3 poems, 5,000 words of prose, and 6 images. Please email all submissions and questions to west10th.submissions@gmail.comMore information can be found on our submissions page.We can't wait to see your submissions!

We're coming out of our summer hiding to briefly say, we love this project! So much lovely language and collaborative fun.Also, to all who have emailed, and to those who have wondered silently, we will begin accepting submissions for the 2012-2013 edition of West 10th in September, which is only a few weeks away, so get writing/arting while summer lasts!

Congratulations to the new editorial board! We received a record number of applications this year, and after much deliberation, Lauren and I feel confident that we have selected the strongest, most cohesive group possible. We can't wait to start work on the magazine again next year.

Editor-In-Chief: Laura Stephenson

Managing Editor: Lauren Roberts

Poetry Editors: Maeve Nolan, Beau Peregoy

Assistant Poetry Editors: Jarry Lee, Joe Masco, Amanda Montell, Eric Stiefel

Prose Editors: Zonia Ali, Conor Burnett

Assistant Prose Editors: Caroline Calloway, Katelyn Lovejoy, Benjamin Miller, Meredith Sharpe

Art Editors: Laura Hetzel, Michelle Ling

Copyeditors: Olivia Loving, Rebecca Rae, Emma Sullivan

See you in the fall!