Maurice - E.M. Forster (1913)

Written in 1913 but only published posthumously in 1971,

Maurice was well ahead of its time in its nuanced depiction of a young man discovering and coming to terms with his sexuality. While Forster carefully examines the difficulties of identity and love,

Maurice is ultimately founded on the belief that same-sex relationships have the capacity to be profound, beautiful and happy—a radical thesis for a novel written when men were still routinely arrested and imprisoned for having sex with other men.

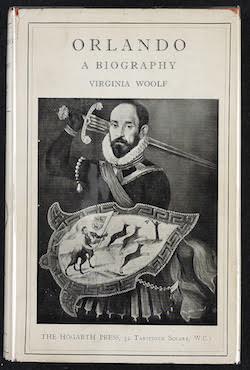

Orlando - Virginia Woolf (1928)

Subtitled “A Biography,”

Orlando was written as a paean to Woolf’s friend and erstwhile lover, the aristocratic Vita Sackville-West. With typical élan, Woolf transforms Sackville-West into the novel’s eponymous protagonist, a sex-changing immortal who begins as an Elizabethan nobleman and ends as a successful female author in ‘the present day’ (that is to say, 1928). Traversing three hundred years of Orlando’s life, Woolf relentlessly questions conventional notions of history, authorship, gender and sexuality.

Nightwood - Djuna Barnes (1936)

Contained in a deceptively slim volume,

Nightwood is a superbly stylized portrait of a doomed lesbian relationship in the bohemian Paris of the interwar years, explicated through the head-spinning speeches of Dr. Matthew-Mighty-grain-of-salt-Dante-O'Conner (who is just as campy as his name suggests). This modernist masterpiece was lauded by T.S. Eliot as “so good a novel that only sensibilities trained on poetry can wholly appreciate it.”

Notre Dame des Fleurs/Our Lady of the Flowers - Jean Genet (1943)

Similarly to

Nightwood, this novel renders the Parisian underworld in prose so rich and revelatory it practically creates a new class of literature. The lives and loves of its central characters—sex workers, trans women, and teenage murderers, all bearing charming monikers like Divine and Darling Daintyfoot—are unspooled by a capricious narrator who creates the world of the novel while masturbating in his prison cell (!!!).

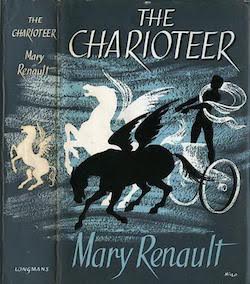

The Charioteer - Mary Renault (1953)Renault, having worked as nurse at a British military hospital during the Second World

War and later emigrated to South Africa to live with her female partner, was uniquely equipped to write this novel, which follows a British soldier who falls in love twice over as he recovers from a combat wound. With equal measures of heartfelt psychological insight and cutting social observation,

The Charioteer struggles with the tensions between idealism and reality, individualism and community, and innocence and experience.

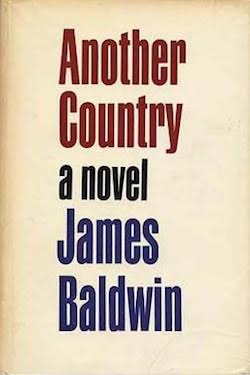

Another Country - James Baldwin (1962)An earlier novel of Baldwin’s,

Giovanni’s Room, is often hailed as a masterpiece of gay literature, but while

Giovanni’s Room is a claustrophobic investigation of one man’s psychology,

Another Country seems to encompass an era.

The characters are gay, straight, bisexual, questioning and in denial; white and black; working-class and middle-class and destitute and wildly successful. In a rhythm reminiscent of jazz, the novel traces the cast as they move in and out of each other’s lives, coupling and splitting up and getting back together, rising and falling in fortune—but always circling around the specter of a character who commits suicide at the end of the novel’s first act.

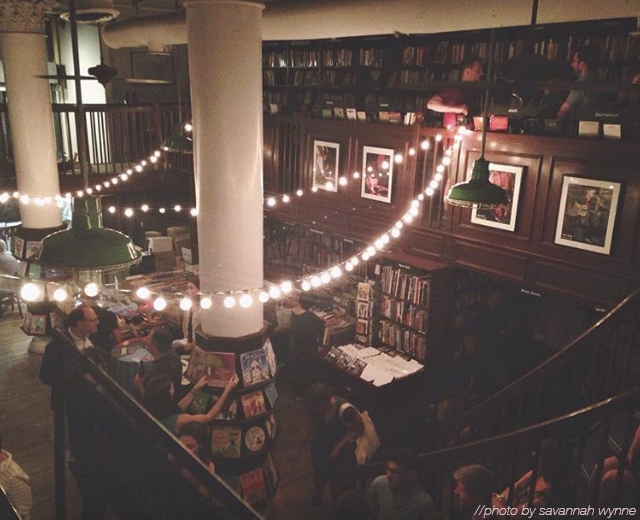

High: Making plans with a literary-minded friend to attend a StorySLAM and getting excited about the night’s theme—something like “Doubt” or “Haunted” or “Hot Mess.”Low: Sneaking your phone out during class or work at exactly 3 pm the week before the event, refreshing the page every few seconds, in order to snag tickets before they sell out.Low: Joining one of two massive lines outside of the Housing Works Bookstore Café nearly an hour before doors open, then flooding inside when they do, desperate to score a seat (or a stair).High: Hearing the storytellers’ intriguing and hilarious first lines.

High: Making plans with a literary-minded friend to attend a StorySLAM and getting excited about the night’s theme—something like “Doubt” or “Haunted” or “Hot Mess.”Low: Sneaking your phone out during class or work at exactly 3 pm the week before the event, refreshing the page every few seconds, in order to snag tickets before they sell out.Low: Joining one of two massive lines outside of the Housing Works Bookstore Café nearly an hour before doors open, then flooding inside when they do, desperate to score a seat (or a stair).High: Hearing the storytellers’ intriguing and hilarious first lines. Low: Uncomfortably laughing when storytellers tell inappropriate or overtly graphic sexual stories.High: Hearing the storytellers nail their last lines.Low: Uncomfortably laughing when the storytellers’ jokes don’t quite hit.High: Seeing a storyteller take the mic for the first time and deliver one of the best stories of the night.High: Cracking up at the host’s on-the-spot reactions to the audience’s write-in stories.High: Noticing the diversity and friendliness of the crowd (though, admittedly, a high percentage of audience members are carrying publishers’ tote bags).High: Laughing collectively for two hours at the woes of living in New York, at the quirks of being a literature lover, and at the woes and quirks of being a literature lover living in New York.--Alyssa Matesic, Editor-in-Chief

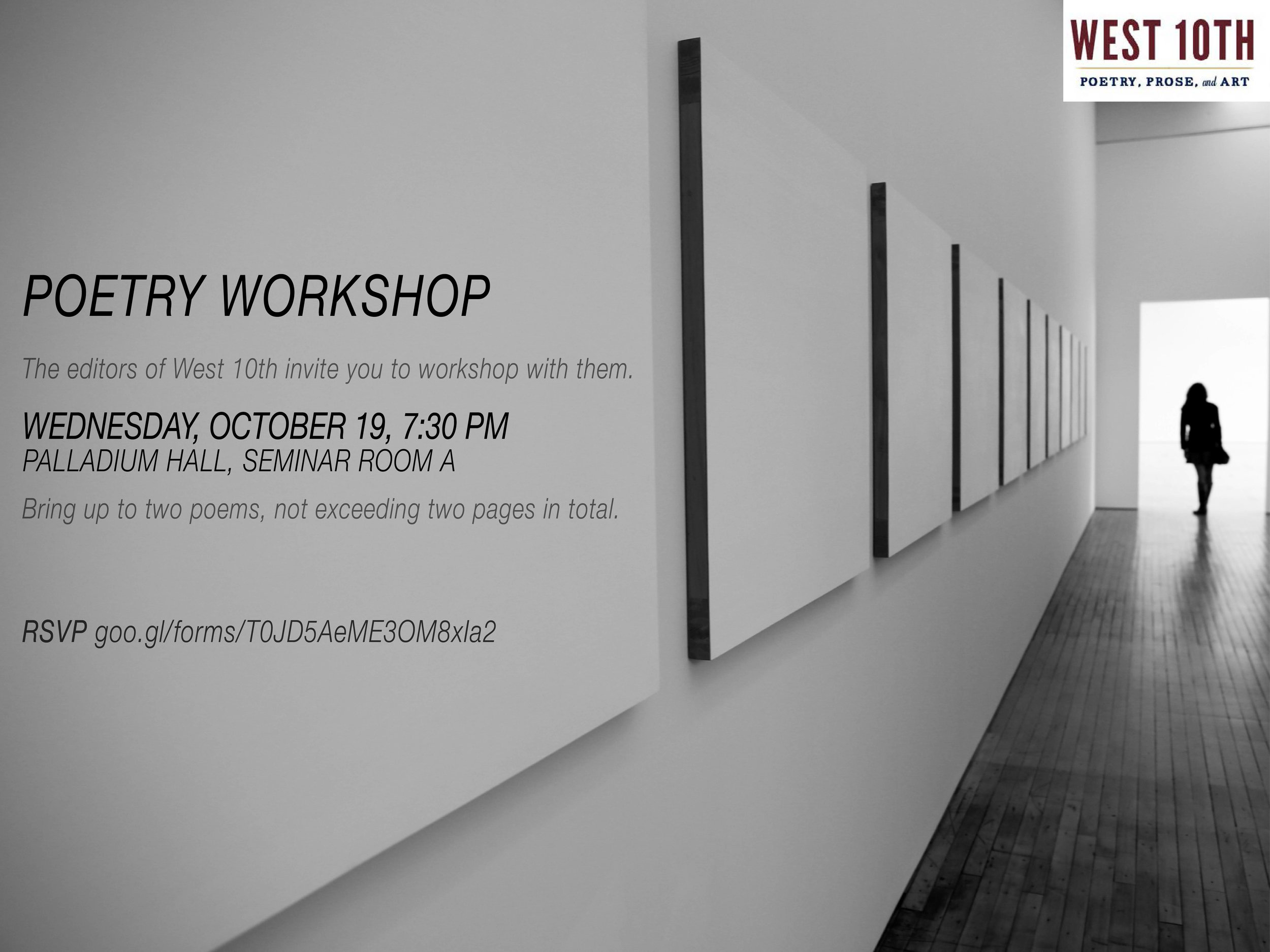

Low: Uncomfortably laughing when storytellers tell inappropriate or overtly graphic sexual stories.High: Hearing the storytellers nail their last lines.Low: Uncomfortably laughing when the storytellers’ jokes don’t quite hit.High: Seeing a storyteller take the mic for the first time and deliver one of the best stories of the night.High: Cracking up at the host’s on-the-spot reactions to the audience’s write-in stories.High: Noticing the diversity and friendliness of the crowd (though, admittedly, a high percentage of audience members are carrying publishers’ tote bags).High: Laughing collectively for two hours at the woes of living in New York, at the quirks of being a literature lover, and at the woes and quirks of being a literature lover living in New York.--Alyssa Matesic, Editor-in-Chief Bring up to two works of poetry (two pages maximum) to receive some feedback from your West 10th Editors. See you there!Just a reminder that we are still

Bring up to two works of poetry (two pages maximum) to receive some feedback from your West 10th Editors. See you there!Just a reminder that we are still  It's that time of the year again! West 10th is now accepting submissions of prose, poetry, and art for its 2016-2017 edition, releasing this spring.Check out West 10th's submission guidelines

It's that time of the year again! West 10th is now accepting submissions of prose, poetry, and art for its 2016-2017 edition, releasing this spring.Check out West 10th's submission guidelines  We are pleased to announce that the 2015-2016 issue of West 10th is complete. To celebrate, we are holding a launch party at the Lillian Vernon Creative Writers House featuring readings by our contributors and a reading by our interviewee, Mira Jacob (acclaimed author of The Sleepwalker's Guide to Dancing). This event is open to the public and refreshments will be served. Come grab a copy of West 10th!

We are pleased to announce that the 2015-2016 issue of West 10th is complete. To celebrate, we are holding a launch party at the Lillian Vernon Creative Writers House featuring readings by our contributors and a reading by our interviewee, Mira Jacob (acclaimed author of The Sleepwalker's Guide to Dancing). This event is open to the public and refreshments will be served. Come grab a copy of West 10th!

Written in 1913 but only published posthumously in 1971, Maurice was well ahead of its time in its nuanced depiction of a young man discovering and coming to terms with his sexuality. While Forster carefully examines the difficulties of identity and love, Maurice is ultimately founded on the belief that same-sex relationships have the capacity to be profound, beautiful and happy—a radical thesis for a novel written when men were still routinely arrested and imprisoned for having sex with other men.

Written in 1913 but only published posthumously in 1971, Maurice was well ahead of its time in its nuanced depiction of a young man discovering and coming to terms with his sexuality. While Forster carefully examines the difficulties of identity and love, Maurice is ultimately founded on the belief that same-sex relationships have the capacity to be profound, beautiful and happy—a radical thesis for a novel written when men were still routinely arrested and imprisoned for having sex with other men.  Subtitled “A Biography,” Orlando was written as a paean to Woolf’s friend and erstwhile lover, the aristocratic Vita Sackville-West. With typical élan, Woolf transforms Sackville-West into the novel’s eponymous protagonist, a sex-changing immortal who begins as an Elizabethan nobleman and ends as a successful female author in ‘the present day’ (that is to say, 1928). Traversing three hundred years of Orlando’s life, Woolf relentlessly questions conventional notions of history, authorship, gender and sexuality. Nightwood - Djuna Barnes (1936)

Subtitled “A Biography,” Orlando was written as a paean to Woolf’s friend and erstwhile lover, the aristocratic Vita Sackville-West. With typical élan, Woolf transforms Sackville-West into the novel’s eponymous protagonist, a sex-changing immortal who begins as an Elizabethan nobleman and ends as a successful female author in ‘the present day’ (that is to say, 1928). Traversing three hundred years of Orlando’s life, Woolf relentlessly questions conventional notions of history, authorship, gender and sexuality. Nightwood - Djuna Barnes (1936) Contained in a deceptively slim volume, Nightwood is a superbly stylized portrait of a doomed lesbian relationship in the bohemian Paris of the interwar years, explicated through the head-spinning speeches of Dr. Matthew-Mighty-grain-of-salt-Dante-O'Conner (who is just as campy as his name suggests). This modernist masterpiece was lauded by T.S. Eliot as “so good a novel that only sensibilities trained on poetry can wholly appreciate it.” Notre Dame des Fleurs/Our Lady of the Flowers - Jean Genet (1943)

Contained in a deceptively slim volume, Nightwood is a superbly stylized portrait of a doomed lesbian relationship in the bohemian Paris of the interwar years, explicated through the head-spinning speeches of Dr. Matthew-Mighty-grain-of-salt-Dante-O'Conner (who is just as campy as his name suggests). This modernist masterpiece was lauded by T.S. Eliot as “so good a novel that only sensibilities trained on poetry can wholly appreciate it.” Notre Dame des Fleurs/Our Lady of the Flowers - Jean Genet (1943) Similarly to Nightwood, this novel renders the Parisian underworld in prose so rich and revelatory it practically creates a new class of literature. The lives and loves of its central characters—sex workers, trans women, and teenage murderers, all bearing charming monikers like Divine and Darling Daintyfoot—are unspooled by a capricious narrator who creates the world of the novel while masturbating in his prison cell (!!!). The Charioteer - Mary Renault (1953)Renault, having worked as nurse at a British military hospital during the Second World

Similarly to Nightwood, this novel renders the Parisian underworld in prose so rich and revelatory it practically creates a new class of literature. The lives and loves of its central characters—sex workers, trans women, and teenage murderers, all bearing charming monikers like Divine and Darling Daintyfoot—are unspooled by a capricious narrator who creates the world of the novel while masturbating in his prison cell (!!!). The Charioteer - Mary Renault (1953)Renault, having worked as nurse at a British military hospital during the Second World  War and later emigrated to South Africa to live with her female partner, was uniquely equipped to write this novel, which follows a British soldier who falls in love twice over as he recovers from a combat wound. With equal measures of heartfelt psychological insight and cutting social observation, The Charioteer struggles with the tensions between idealism and reality, individualism and community, and innocence and experience. Another Country - James Baldwin (1962)An earlier novel of Baldwin’s, Giovanni’s Room, is often hailed as a masterpiece of gay literature, but while Giovanni’s Room is a claustrophobic investigation of one man’s psychology, Another Country seems to encompass an era.

War and later emigrated to South Africa to live with her female partner, was uniquely equipped to write this novel, which follows a British soldier who falls in love twice over as he recovers from a combat wound. With equal measures of heartfelt psychological insight and cutting social observation, The Charioteer struggles with the tensions between idealism and reality, individualism and community, and innocence and experience. Another Country - James Baldwin (1962)An earlier novel of Baldwin’s, Giovanni’s Room, is often hailed as a masterpiece of gay literature, but while Giovanni’s Room is a claustrophobic investigation of one man’s psychology, Another Country seems to encompass an era.  The characters are gay, straight, bisexual, questioning and in denial; white and black; working-class and middle-class and destitute and wildly successful. In a rhythm reminiscent of jazz, the novel traces the cast as they move in and out of each other’s lives, coupling and splitting up and getting back together, rising and falling in fortune—but always circling around the specter of a character who commits suicide at the end of the novel’s first act.

The characters are gay, straight, bisexual, questioning and in denial; white and black; working-class and middle-class and destitute and wildly successful. In a rhythm reminiscent of jazz, the novel traces the cast as they move in and out of each other’s lives, coupling and splitting up and getting back together, rising and falling in fortune—but always circling around the specter of a character who commits suicide at the end of the novel’s first act. This workshop is open to all undergrad students! So bring up to 1500 words of fiction/non-fiction prose to receive some feedback and comments from your West 10th Editors.Just a reminder that we are still

This workshop is open to all undergrad students! So bring up to 1500 words of fiction/non-fiction prose to receive some feedback and comments from your West 10th Editors.Just a reminder that we are still