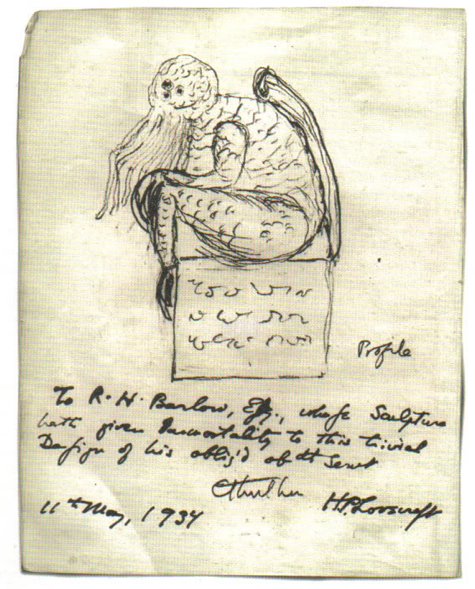

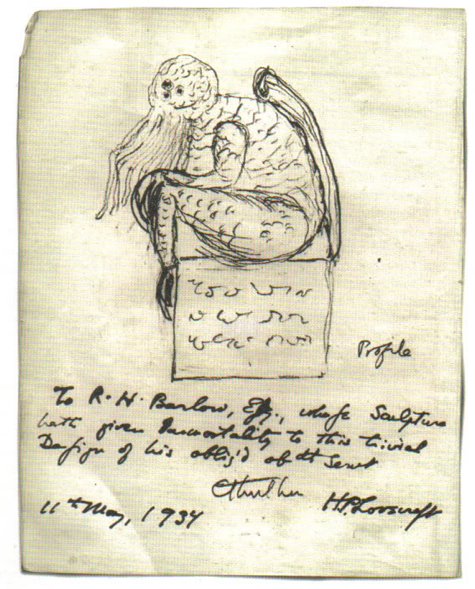

“The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown” – H.P. Lovecraft, Supernatural Horror in Literature  An excerpt from H.P. Lovecraft’s notes (1928), where he first doodled the creature of the Cthulhu. An imitation of H.P. Lovecraft, by Benjamin Mok: There is a house in Providence, down the lane from Prospect Park. Beneath a roof reminiscent of American colonial architecture, shuttered windows line the two floors, a façade of suburban normality betrayed by the gothic archway inviting you in. You walk past the cramped entranceway where worn, ornate furniture is crammed haphazardly throughout, each piece dreaming of a time when they inhabited grander mansions than this. Victorian portraits glare down at you from every available space on the walls, angered by your intrusion. Up the stairs, the door to the study stands ajar, framing a figure hunched over a mahogany desk. He doesn’t look up as you enter the room. A single window watches over his lanky, bespectacled form, faint moonlight illuminating the yellowed pulp magazines mixed into untidy sheaves of manuscript piled up around him. It is silent in this room, save for the faint ‘skritch-skritch’ of ballpoint against paper. You draw closer and notice another presence in the room standing beside the man, one that you could have sworn was not there a moment before. Vaguely human, dark as crude oil, its rubbery skin gleams beneath the moonlight. It rests its membranous hands lightly on the shoulder of the man, arching its slender form over the desk, as if perusing his work as it is written. You take a step back. It looks up, and where a face would have been there is nothing but skin stretched around an oval skull, the only indication of its eyes the two sunken depressions staring back at you. It raises a single, webbed finger to where its lips should have been. The moonlight flickers. You flee, past down the creaking stairs that whine with every step, out through the open front door (did you leave it open before?) and out into… Normality. Or do you? That is the question Lovecraft confronts us with, in his massive, underrated body of work known collectively as the Lovecraft mythos. In it, readers are confronted with esoteric mythology, mind-numbing descriptions that defy conception, and an expansive bestiary of monstrosities–all framed within a seductive mixture of noir pulp fiction and cosmic horror. Known today as one of the progenitors of the ‘weird fiction’ genre, Howard Phillips Lovecraft once described the uniqueness of his work, and of the sub-genre it inspired, as thus:“The true weird tale has something more than secret murder, bloody bones, or a sheeted form clanking chains according to rule. A certain atmosphere of breathless and unexplainable dread of outer, unknown forces must be present; and there must be a hint, expressed with a seriousness and portentousness becoming its subject, of that most terrible conception of the human brain—a malign and particular suspension or defeat of those fixed laws of Nature which are our only safeguard against the assaults of chaos and the daemons of unplumbed space.”[Lovecraft, Supernatural Horror in Literature]A self-styled “antiquarian,” Lovecraft drew upon his knowledge of mythology, as viewed through the lens of anthropological and historical research at the time, in order to craft a convincing illusion of otherworldly forces and entities at work within realistic, contemporary settings. Lovecraft was a master at generating atmosphere in his work, an oppressive tension that permeates his breathless descriptions of non-Euclidian architecture and gruesome creatures. As with much of the work produced within weird fiction, it was this exact style of writing that drove as many away from reading his work as it has drawn to it. Worse, there exists within his work hints of a very real fear within the society of his time. This fear functioned along the same lines as the cosmic terror Lovecraft peddled, but had consequences beyond the titillation of the mind and shuddering of the heart–the fear of the ‘other,’ framed as the unknowable. Modern scholars and biographers of Lovecraft have since pointed out concrete evidence with regards to his racist worldview, centered about a conviction in the cultural superiority of the Anglo-Saxon races, and a pseudo-scientific belief in eugenics. Much of this analysis can be found in the work of the premier Lovecraftian scholar, S.T. Joshi, in the biography: I Am Providence.Yet, regardless of literary and social controversy, his mythos has since taken on a life of its own within our cultural spheres, ranging from a still-growing legacy of Lovecraftian horror fiction that pays direct homage to Lovecraft as it expands the mythology established by him, to pop culture commercialism expressed in Cthulhu plushies and Lovecraft tote bags, to its inspiration of contemporary producers of horror such as Stephen King, Alan Moore and Junji Ito. Despite the literary snobbishness that Lovecraft’s works faced and still faces today, as with most genre fiction tending towards the fantastic, the proliferation of his ideas and motifs within society today tells us that there’s something important about cosmic horror that is worthy of our attention. What exactly was he so interested in? Lovecraft himself stated that he was fascinated by the notion of ‘cosmicism:’ that the human race was insignificant, vulnerable, and ultimately doomed in its existence within an arbitrary universe. To Lovecraft, notions of spirituality and universality were at best, forms of ideology, and at worst, superstition. No doubt that this was in part at least influenced by the transition of Anglo-European society into modernity, whereby both lingering religious beliefs and Enlightenment-era ideals were crushed bythe savagery of the World Wars. At a time in which the promise of science revealed more questions than answers (or reached towards answers that led to warped perspectives as was the case in eugenics), the morbid appeal of the specters of the past began to be replaced with the appeal of the sublime. The sublime, without getting too much into the philosophical aspects of 18th-century Romantic poetry from which Lovecraft drew inspiration, is generally considered to be the ‘presentation of an indeterminate concept of reason’–a definition coined by Immanuel Kant in 1790. Whereas beauty is only a temporary response gained through understanding an object, the sublime refers to a ‘realm of experience beyond the measurable,’ dependent upon the unknowable nature of the object in question. What is sublime then must also evoke in equal parts terror and awe, resulting in an ecstasy that is ‘beyond oneself.’ One of the best explanations of the sublime I have come across can be found here. As Kant claims, only humans are capable of experiencing the sublime, for only we (as far as we know) have forgotten our insignificance in the face of nature, having grown arrogant in our dominance over the most easily observed aspects of it. The concept of death, for example, is something that we pretend to internalize, just so we might function in the day-to-day without being paralyzed by existential terror. Yet, who amongst us is able to give a definite answer of what lies beyond the veil?In many ways, the question of what the sublime is lies at the very core of horror fiction, as not only must the sublime invoke terror and awe, it must also elicit the inherent ‘pleasure’ of emotions: a freedom from oneself that can only be experienced when faced with the ego-destroying nature of infinity, or death. Of course, not everyone consumes works of horror in order to pummel themselves with existential crises, but there is a portion of ourselves that will always, unconsciously, be subject to the anxiety of not knowing what exists beyond the boundaries established by science. That is what art concerned with the sublime taps into. Lovecraft’s fascination with the sublime was what led him to pen some of his greatest works. In The Shadow Out of Time, Lovecraft deals with the science fiction trope of time travel in a characteristically morbid fashion–Nathaniel Wingate Peaslee, an American living in the 1930s finds himself possessed by an alien known as a Yithian, causing him to occasionally break out into visions of the past, present and future. Through them, he experiences the lives of these otherworldly entities, his consciousness transplanted into the monstrous form of the Yithians possessing him. His travels take him from the earliest reaches of the known history, from the Palaeozoic Era to the speculated future, which Lovecraft chose to be 16,000 A.D. Yet, upon returning to his body, he finds that society has deemed him insane due to the seemingly mad actions of the Yithian. Throughout the vast scope of the work, Nathaniel grows increasingly uncertain about the state of his own sanity as he struggles with the revelations–a masterful treatment of paranoia that was, to a certain extent, fuelled by Lovecraft’s. Yet, it is worth noting that Lovecraft made specific emphasis on how his protagonist’s troubles were brought about by “a lean, dark, curiously foreign-looking man,” and that in 16,000 A.D., his protagonist had spoken with “a magician of the dark conquerors.” Seems harmless? Let us take a look at another piece of work he penned then – The Horror at Red Hook. Here, Lovecraft talks about how Aryan civilization was all that stood against the “primitive half-ape savagery” of the lesser races, as evidenced by the poor neighborhoods of New York. Or, looking further back, we find a doggerel poem penned by Lovecraft, titled “On the Creation of Niggers,” where he states that “to fill the gap, to join the rest to Man,” God had created a beast “in semi-human figure, filled it with vice, and called the thing a Nigger.”This is unsurprising to anyone who already knows of Lovecraft’s beliefs. As an amateur journalist in 1915, Lovecraft had penned an article stating that “the crime of the century” was not that World War I had occurred, but that “the unnatural racial alignment of the various warring power” had led the Anglo-Saxon race to align themselves with “lesser breeds.” Later, he was to become an avid proponent of eugenics and racial Darwinism, masking his racism with an affectation of 18th-century colonial aristocratism. In another letter, he decried the invasion of American cities by ‘hook-nosed, swarthy, guttural-voiced’ Jews, “flabby, pungent, grinning, chattering niggers,” and “undesirable Latins, low-grade Southern Italians and Portuguese, and the clamorous plague of French-Canadians.” Even for the standards of early-19th century American society, the extent of his racism was beyond the norm–one that he was in the end unwilling to change with the changing times.His treatment of women was no better. He denigrated Jewish people and culture in front of his wife, Sonia Greene, who was herself Jewish and repeatedly tried to remind him “about her own background, but it didn’t seem to dissuade him from his fear of Jews and other immigrants.” Instead, he told her that she “no longer belonged to these mongrels.” In his work, he regularly fetishized women as the monsters from his mythos, clothed in a deceptive form, or portrayed as crones stemming from New England superstitions of witches (drawing inspiration from the Salem witch trials). In The Thing on the Doorstep, a piece he wrote in 1933, he castigates a character named Asenath Waite, whose abnormal desire was that “she wanted to be a man,” and thus abducted, then stole the form of the male protagonist. Stephen King, who names Lovecraft amongst one of his chief inspirations, has admitted that The Dunwich Horror and At the Mountains of Madness are works “about sex and little else,” and that the iconic Cthulhu was “a gigantic, tentacle-equipped, killer vagina from beyond space and time.” Arguing that Lovecraft was a product of his time is no excuse–as we have seen, his tendencies towards passionate racism and sexism extended beyond cultural indoctrination, wrapped into a mission and ideal of ‘civilization.’ Underlying his exploration of otherworldly terror lies a fear that in the globalization and economic decline during the turn of the 19th century, the patriarchal “Anglo-Saxon” civilization was in danger of being destroyed. As much as Lovecraft wrote about gruesome monsters and mind-bending architecture, the bulk of his work was an exploration of the clinical depression from which he suffered, the notion of ‘undeath’ that he focused on obsessively. Yet, that does not mean he possessed a more nuanced understanding of people. In a 1921 letter, he also wrote: “I could not write about ‘ordinary people’ because I am not in the least interested in them. Without interest there can be no art… the humanocentric pose is impossible to me, for I cannot acquire the primitive myopia which magnifies the earth and ignores the background.” Perhaps then, while Lovecraft was eager to gaze at the stars, his reluctance to adopt this ‘primitive myopia’ prevented him from actually magnifying the earth, and taking a good look at the people around him. The reason why discussing Lovecraft is difficult is because the project he engaged in still has significance today. The knowledge of the sublime is something we all carry around with us, in our conversations with aging parents, in our irrational fears for our health, in our news outlets projecting images of death and destruction into our eyes. The more science reveals to us, the more we find ourselves subject to an uncaringly vast universe. It is still important that we express the sheer terror of existence, a collective lack of knowledge about what’s across that veil, in our cultural work today–and many do, in spheres ranging from the literary, to the popular.As we see with Lovecraft, it is easy to merge this concept of the sublime with a passionate hate and distrust of the ‘other,’ to what are conceived as social abnormalities or breaches of morality. Lovecraft certainly engaged in this, with a mythological construction of the ‘other’ designed to assail readers with uneasy imagery and concepts. Yet, in our perception of morality today, we clearly identify his faults, his racism, and his fetishization of violence towards women. Faced with this question, those influenced by his legacy find it difficult to resolve this tension. World Fantasy Award-winning novelist Nnedi Okorafor’s wrote a blog post in 2011, in response to a controversy regarding the replacement of Lovecraft’s bust as the award, stating that she wanted to “face the history of this leg of literature rather than put it aside or bury it.” People of a wide range of ethnicities and gender not only enjoy Lovecraft’s work, but produce more within his mythos–much of which criticizes and deconstructs Lovecraft’s prejudice, while still drawing upon his vision to create an unique literary sub-genre. The lesson then, if there is one to be learnt here, is that existential terror, conceived to be both awesome and terrible, but most importantly universal, can easily be turned into an aversion to anything outside of constructed social norms. It after all, taps into our deepest fears and the questions we have left unanswered. In our desperation for an answer, it becomes easy for us to direct this universal fear at a particular target. And recognizing this, cultural producers continue to use fear as a political and commercial tool.Yet, does this have to be the case? What about the other half of the sublime–the awe which it is supposed to inspire? There is much that has evolved within the sub-genre of weird fiction. While I dislike much of Tim Burton’s work, especially recently, I still remember watching Corpse Bride when I was young–an experience of the ‘weird’ that did not create fear, but a comfortable joy. Weird fiction is today in the process of taking a turn towards a celebration of the abnormal and the unknown, rather than fetishizing and fearing it. Instead of relying on politicians and media telling us which societal/ethnic group it is ‘in fashion’ to celebrate, perhaps we should look more carefully at the culture which we consume, and change it. A proper appreciation of the sublime gives us a toolkit to critically thinking beyond empirical norms, and allows us to judge for ourselves what is beyond the veil–a real authenticity in our pursuit for morality. Happy Halloween!P.S.: If you haven’t yet, check out Junji Ito’s work. It will leave a chill running down your spine.

An excerpt from H.P. Lovecraft’s notes (1928), where he first doodled the creature of the Cthulhu. An imitation of H.P. Lovecraft, by Benjamin Mok: There is a house in Providence, down the lane from Prospect Park. Beneath a roof reminiscent of American colonial architecture, shuttered windows line the two floors, a façade of suburban normality betrayed by the gothic archway inviting you in. You walk past the cramped entranceway where worn, ornate furniture is crammed haphazardly throughout, each piece dreaming of a time when they inhabited grander mansions than this. Victorian portraits glare down at you from every available space on the walls, angered by your intrusion. Up the stairs, the door to the study stands ajar, framing a figure hunched over a mahogany desk. He doesn’t look up as you enter the room. A single window watches over his lanky, bespectacled form, faint moonlight illuminating the yellowed pulp magazines mixed into untidy sheaves of manuscript piled up around him. It is silent in this room, save for the faint ‘skritch-skritch’ of ballpoint against paper. You draw closer and notice another presence in the room standing beside the man, one that you could have sworn was not there a moment before. Vaguely human, dark as crude oil, its rubbery skin gleams beneath the moonlight. It rests its membranous hands lightly on the shoulder of the man, arching its slender form over the desk, as if perusing his work as it is written. You take a step back. It looks up, and where a face would have been there is nothing but skin stretched around an oval skull, the only indication of its eyes the two sunken depressions staring back at you. It raises a single, webbed finger to where its lips should have been. The moonlight flickers. You flee, past down the creaking stairs that whine with every step, out through the open front door (did you leave it open before?) and out into… Normality. Or do you? That is the question Lovecraft confronts us with, in his massive, underrated body of work known collectively as the Lovecraft mythos. In it, readers are confronted with esoteric mythology, mind-numbing descriptions that defy conception, and an expansive bestiary of monstrosities–all framed within a seductive mixture of noir pulp fiction and cosmic horror. Known today as one of the progenitors of the ‘weird fiction’ genre, Howard Phillips Lovecraft once described the uniqueness of his work, and of the sub-genre it inspired, as thus:“The true weird tale has something more than secret murder, bloody bones, or a sheeted form clanking chains according to rule. A certain atmosphere of breathless and unexplainable dread of outer, unknown forces must be present; and there must be a hint, expressed with a seriousness and portentousness becoming its subject, of that most terrible conception of the human brain—a malign and particular suspension or defeat of those fixed laws of Nature which are our only safeguard against the assaults of chaos and the daemons of unplumbed space.”[Lovecraft, Supernatural Horror in Literature]A self-styled “antiquarian,” Lovecraft drew upon his knowledge of mythology, as viewed through the lens of anthropological and historical research at the time, in order to craft a convincing illusion of otherworldly forces and entities at work within realistic, contemporary settings. Lovecraft was a master at generating atmosphere in his work, an oppressive tension that permeates his breathless descriptions of non-Euclidian architecture and gruesome creatures. As with much of the work produced within weird fiction, it was this exact style of writing that drove as many away from reading his work as it has drawn to it. Worse, there exists within his work hints of a very real fear within the society of his time. This fear functioned along the same lines as the cosmic terror Lovecraft peddled, but had consequences beyond the titillation of the mind and shuddering of the heart–the fear of the ‘other,’ framed as the unknowable. Modern scholars and biographers of Lovecraft have since pointed out concrete evidence with regards to his racist worldview, centered about a conviction in the cultural superiority of the Anglo-Saxon races, and a pseudo-scientific belief in eugenics. Much of this analysis can be found in the work of the premier Lovecraftian scholar, S.T. Joshi, in the biography: I Am Providence.Yet, regardless of literary and social controversy, his mythos has since taken on a life of its own within our cultural spheres, ranging from a still-growing legacy of Lovecraftian horror fiction that pays direct homage to Lovecraft as it expands the mythology established by him, to pop culture commercialism expressed in Cthulhu plushies and Lovecraft tote bags, to its inspiration of contemporary producers of horror such as Stephen King, Alan Moore and Junji Ito. Despite the literary snobbishness that Lovecraft’s works faced and still faces today, as with most genre fiction tending towards the fantastic, the proliferation of his ideas and motifs within society today tells us that there’s something important about cosmic horror that is worthy of our attention. What exactly was he so interested in? Lovecraft himself stated that he was fascinated by the notion of ‘cosmicism:’ that the human race was insignificant, vulnerable, and ultimately doomed in its existence within an arbitrary universe. To Lovecraft, notions of spirituality and universality were at best, forms of ideology, and at worst, superstition. No doubt that this was in part at least influenced by the transition of Anglo-European society into modernity, whereby both lingering religious beliefs and Enlightenment-era ideals were crushed bythe savagery of the World Wars. At a time in which the promise of science revealed more questions than answers (or reached towards answers that led to warped perspectives as was the case in eugenics), the morbid appeal of the specters of the past began to be replaced with the appeal of the sublime. The sublime, without getting too much into the philosophical aspects of 18th-century Romantic poetry from which Lovecraft drew inspiration, is generally considered to be the ‘presentation of an indeterminate concept of reason’–a definition coined by Immanuel Kant in 1790. Whereas beauty is only a temporary response gained through understanding an object, the sublime refers to a ‘realm of experience beyond the measurable,’ dependent upon the unknowable nature of the object in question. What is sublime then must also evoke in equal parts terror and awe, resulting in an ecstasy that is ‘beyond oneself.’ One of the best explanations of the sublime I have come across can be found here. As Kant claims, only humans are capable of experiencing the sublime, for only we (as far as we know) have forgotten our insignificance in the face of nature, having grown arrogant in our dominance over the most easily observed aspects of it. The concept of death, for example, is something that we pretend to internalize, just so we might function in the day-to-day without being paralyzed by existential terror. Yet, who amongst us is able to give a definite answer of what lies beyond the veil?In many ways, the question of what the sublime is lies at the very core of horror fiction, as not only must the sublime invoke terror and awe, it must also elicit the inherent ‘pleasure’ of emotions: a freedom from oneself that can only be experienced when faced with the ego-destroying nature of infinity, or death. Of course, not everyone consumes works of horror in order to pummel themselves with existential crises, but there is a portion of ourselves that will always, unconsciously, be subject to the anxiety of not knowing what exists beyond the boundaries established by science. That is what art concerned with the sublime taps into. Lovecraft’s fascination with the sublime was what led him to pen some of his greatest works. In The Shadow Out of Time, Lovecraft deals with the science fiction trope of time travel in a characteristically morbid fashion–Nathaniel Wingate Peaslee, an American living in the 1930s finds himself possessed by an alien known as a Yithian, causing him to occasionally break out into visions of the past, present and future. Through them, he experiences the lives of these otherworldly entities, his consciousness transplanted into the monstrous form of the Yithians possessing him. His travels take him from the earliest reaches of the known history, from the Palaeozoic Era to the speculated future, which Lovecraft chose to be 16,000 A.D. Yet, upon returning to his body, he finds that society has deemed him insane due to the seemingly mad actions of the Yithian. Throughout the vast scope of the work, Nathaniel grows increasingly uncertain about the state of his own sanity as he struggles with the revelations–a masterful treatment of paranoia that was, to a certain extent, fuelled by Lovecraft’s. Yet, it is worth noting that Lovecraft made specific emphasis on how his protagonist’s troubles were brought about by “a lean, dark, curiously foreign-looking man,” and that in 16,000 A.D., his protagonist had spoken with “a magician of the dark conquerors.” Seems harmless? Let us take a look at another piece of work he penned then – The Horror at Red Hook. Here, Lovecraft talks about how Aryan civilization was all that stood against the “primitive half-ape savagery” of the lesser races, as evidenced by the poor neighborhoods of New York. Or, looking further back, we find a doggerel poem penned by Lovecraft, titled “On the Creation of Niggers,” where he states that “to fill the gap, to join the rest to Man,” God had created a beast “in semi-human figure, filled it with vice, and called the thing a Nigger.”This is unsurprising to anyone who already knows of Lovecraft’s beliefs. As an amateur journalist in 1915, Lovecraft had penned an article stating that “the crime of the century” was not that World War I had occurred, but that “the unnatural racial alignment of the various warring power” had led the Anglo-Saxon race to align themselves with “lesser breeds.” Later, he was to become an avid proponent of eugenics and racial Darwinism, masking his racism with an affectation of 18th-century colonial aristocratism. In another letter, he decried the invasion of American cities by ‘hook-nosed, swarthy, guttural-voiced’ Jews, “flabby, pungent, grinning, chattering niggers,” and “undesirable Latins, low-grade Southern Italians and Portuguese, and the clamorous plague of French-Canadians.” Even for the standards of early-19th century American society, the extent of his racism was beyond the norm–one that he was in the end unwilling to change with the changing times.His treatment of women was no better. He denigrated Jewish people and culture in front of his wife, Sonia Greene, who was herself Jewish and repeatedly tried to remind him “about her own background, but it didn’t seem to dissuade him from his fear of Jews and other immigrants.” Instead, he told her that she “no longer belonged to these mongrels.” In his work, he regularly fetishized women as the monsters from his mythos, clothed in a deceptive form, or portrayed as crones stemming from New England superstitions of witches (drawing inspiration from the Salem witch trials). In The Thing on the Doorstep, a piece he wrote in 1933, he castigates a character named Asenath Waite, whose abnormal desire was that “she wanted to be a man,” and thus abducted, then stole the form of the male protagonist. Stephen King, who names Lovecraft amongst one of his chief inspirations, has admitted that The Dunwich Horror and At the Mountains of Madness are works “about sex and little else,” and that the iconic Cthulhu was “a gigantic, tentacle-equipped, killer vagina from beyond space and time.” Arguing that Lovecraft was a product of his time is no excuse–as we have seen, his tendencies towards passionate racism and sexism extended beyond cultural indoctrination, wrapped into a mission and ideal of ‘civilization.’ Underlying his exploration of otherworldly terror lies a fear that in the globalization and economic decline during the turn of the 19th century, the patriarchal “Anglo-Saxon” civilization was in danger of being destroyed. As much as Lovecraft wrote about gruesome monsters and mind-bending architecture, the bulk of his work was an exploration of the clinical depression from which he suffered, the notion of ‘undeath’ that he focused on obsessively. Yet, that does not mean he possessed a more nuanced understanding of people. In a 1921 letter, he also wrote: “I could not write about ‘ordinary people’ because I am not in the least interested in them. Without interest there can be no art… the humanocentric pose is impossible to me, for I cannot acquire the primitive myopia which magnifies the earth and ignores the background.” Perhaps then, while Lovecraft was eager to gaze at the stars, his reluctance to adopt this ‘primitive myopia’ prevented him from actually magnifying the earth, and taking a good look at the people around him. The reason why discussing Lovecraft is difficult is because the project he engaged in still has significance today. The knowledge of the sublime is something we all carry around with us, in our conversations with aging parents, in our irrational fears for our health, in our news outlets projecting images of death and destruction into our eyes. The more science reveals to us, the more we find ourselves subject to an uncaringly vast universe. It is still important that we express the sheer terror of existence, a collective lack of knowledge about what’s across that veil, in our cultural work today–and many do, in spheres ranging from the literary, to the popular.As we see with Lovecraft, it is easy to merge this concept of the sublime with a passionate hate and distrust of the ‘other,’ to what are conceived as social abnormalities or breaches of morality. Lovecraft certainly engaged in this, with a mythological construction of the ‘other’ designed to assail readers with uneasy imagery and concepts. Yet, in our perception of morality today, we clearly identify his faults, his racism, and his fetishization of violence towards women. Faced with this question, those influenced by his legacy find it difficult to resolve this tension. World Fantasy Award-winning novelist Nnedi Okorafor’s wrote a blog post in 2011, in response to a controversy regarding the replacement of Lovecraft’s bust as the award, stating that she wanted to “face the history of this leg of literature rather than put it aside or bury it.” People of a wide range of ethnicities and gender not only enjoy Lovecraft’s work, but produce more within his mythos–much of which criticizes and deconstructs Lovecraft’s prejudice, while still drawing upon his vision to create an unique literary sub-genre. The lesson then, if there is one to be learnt here, is that existential terror, conceived to be both awesome and terrible, but most importantly universal, can easily be turned into an aversion to anything outside of constructed social norms. It after all, taps into our deepest fears and the questions we have left unanswered. In our desperation for an answer, it becomes easy for us to direct this universal fear at a particular target. And recognizing this, cultural producers continue to use fear as a political and commercial tool.Yet, does this have to be the case? What about the other half of the sublime–the awe which it is supposed to inspire? There is much that has evolved within the sub-genre of weird fiction. While I dislike much of Tim Burton’s work, especially recently, I still remember watching Corpse Bride when I was young–an experience of the ‘weird’ that did not create fear, but a comfortable joy. Weird fiction is today in the process of taking a turn towards a celebration of the abnormal and the unknown, rather than fetishizing and fearing it. Instead of relying on politicians and media telling us which societal/ethnic group it is ‘in fashion’ to celebrate, perhaps we should look more carefully at the culture which we consume, and change it. A proper appreciation of the sublime gives us a toolkit to critically thinking beyond empirical norms, and allows us to judge for ourselves what is beyond the veil–a real authenticity in our pursuit for morality. Happy Halloween!P.S.: If you haven’t yet, check out Junji Ito’s work. It will leave a chill running down your spine.

Spread the word

Spread the word